“Whenever there is a will there will always be a hill,” Sidney Poitier writes in his 1980 autobiography, This Life, “and wherever there is hope there

“Whenever there is a will there will always be a hill,” Sidney Poitier writes in his 1980 autobiography, This Life, “and wherever there is hope there will always be a chance.”

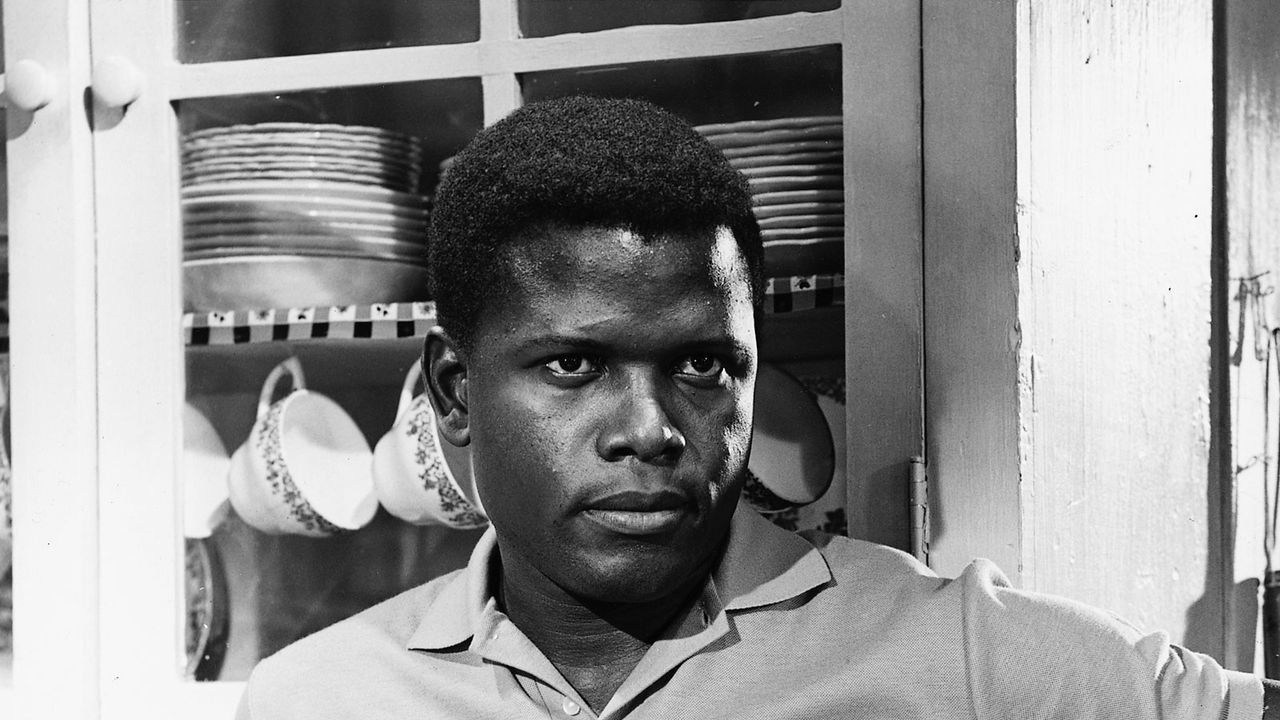

The pioneering, charming, and handsome superstar, celebrated for films like In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, A Raisin in the Sun, The Defiant Ones, A Patch of Blue, and To Sir, With Love, climbed many hills in his long life. He was more than an actor: He was a civil rights activist, diplomat, director, and all-around legend.

But the conversational This Life reveals that Poitier was also so much more: a brilliant, perceptive, witty, self-deprecating, oftentimes lighthearted communicator who told at turns hilarious and poignant stories about everyone from Sammy Davis Jr. to Quincy Jones, Katharine Hepburn, Paul Newman, Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, Dizzy Gillespie, Tony Curtis, Dorothy Dandridge, and Eartha Kitt.

His philosophical, principled, sensitive nature is also evident in Poitier’s 2000 memoir, The Measure of a Man, a beautifully written book of musings from an ever-evolving elder statesman. As he once said: “If I’m remembered for having done a few good things, and if my presence here has sparked some good energies, that’s plenty.”

Little Sidney P

Sidney Poitier was born in Miami on February 20, 1927. Premature and weighing less than three pounds, he was the seventh surviving child of his beloved parents, Evelyn and Reginald—Bahamian tomato farmers who had come to Florida to sell their crop. With her newborn failing to thrive, Evelyn went to a soothsayer who reassured her that petite Sidney would do more than just survive. “He will travel to most of the corners of the earth,” the mystic insisted. “He will walk with kings. He will be rich and famous. Your name will be carried all over the world.”

At three months ancient, Poitier was taken to the family home of Cat Island, which he describes as a needy, “preindustrial” natural paradise, where the tools for survival were taught early. “I was drawn to dangerous things,” he writes. “Ever since I can remember I enjoyed being scared a little bit.” Poitier believes this began when his mother threw him into water at ten months ancient, forcing him to learn to swim.

From the age of four, Poitier was “the captain of his own ship”—even if he was also dressed in clothes fashioned from grain sacks. He poetically conveys the magic of exploring the island, but also indulges in the earthy, raunchy sense of humor amply evident throughout his This Life, even telling one embarrassing tale of failed bestiality with “a good looking chicken.”

This elementary life ended in 1937, when an American embargo on Bahamian tomatoes convinced the Poitiers to move to the capital city of Nassau. He was shocked to see running water, cars, mirrors, ice cream, and cowboy movies. After leaving school at age eleven, he worked manual jobs, lost his virginity to a sex worker (who gave him syphilis), and was arrested for stealing corn.

Worried about the temptations of Nassau, Reginald decided he had to get his son out of town, and put him on a boat to America. “For the first time in my fifteen years, I was on my own,” Poitier writes. “With a small, battered suitcase and three dollars against the world.”

A Rude Arrival

Poitier’s description of his first years in America read like a hero’s journey in a Greek epic, with tests and tribulations at every turn. While living with his brother, Cyril, in Miami, the teen was heartbreakingly introduced to the brutal, racist world of Jim Crow when he was harassed by the Klan for delivering a package to a white woman’s front porch. He was also assaulted by a corrupt cop for being in the wrong part of town.

COMMENTS