In the fall of 1972, John Williams—40 years elderly, the father of three teenagers, a earnest, old-soul musician with nearly 20 years in the business

In the fall of 1972, John Williams—40 years elderly, the father of three teenagers, a earnest, old-soul musician with nearly 20 years in the business—found himself seated across from an excitable, nerdy director, 25 years elderly, who had just been offered his first feature. John, who never paid much heed to the films or TV of his own youth, was encountering a kid from Arizona who worshiped movies—who had been collecting soundtracks since he was 10, and who whistled “Make Me Rainbows” (a song John wrote for the 1967 movie Fitzwilly, starring Dick Van Dyke) to a bemused John during lunch.

Steven Spielberg’s mother, Leah, had trained as a concert pianist and sacrificed a career in music to raise her children. “Steven always had a highly developed imagination,” Leah said in 1986. “He was afraid of everything. When he was little he would insist that I light the top of the [piano] so he could see the strings while I played. Then he would fall on the floor, screaming in fear.” Spielberg’s parents took him to concerts at the nearby Philadelphia Orchestra, where he sat “trapped in between them,” he recalled. “When I wanted to leave, I couldn’t. And it wasn’t because I was bored. It was because I was terrified—because of the power of Stravinsky, the power of Prokofiev, the power of Mahler.”

As a teenager, Spielberg added to his enormous soundtrack collection an album for the 1969 William Faulkner adaptation The Reivers, with an old-fashioned orchestral score by John Williams. He wrote an early screenplay—a story about barnstorming in the 1930s called Ace Eli and Rodger of the Skies—while listening to that album. In a way, Spielberg later said, the screenplay “was based on the music, which I heard so often I wore the record out and had to buy another one. The script never got made. Back then nobody was interested in my big inspirations. I thought, ‘If I ever get a shot at directing a movie, I really want to see if this guy will write the score.’”

Spielberg’s early education permanently shaped his taste in music—how extroverted and tuneful and dominant it could be in a film—separating him from many of his peers in the 1970s. “I’ve always made movies about the things that scare me and, musically, I was attracted to the kind of music that frightened me when I was three, four, five years old,” he explained. He was a traditionalist, in that he wanted scores “to make my movies bigger than I had made them.”

Spielberg played clarinet in his high school bands, and in 1964, at 17, he scored his own feature-length debut, Firelight, composed on clarinet and transposed for his high school orchestra with facilitate from his mother. “If I weren’t a filmmaker,” Spielberg once confessed, “I’d probably be in music. I’d be a starving composer somewhere in Hollywood right now—hopefully not starving, but I probably would not have been successful.”

In 1968, having finagled his way into an apprenticeship on the Universal lot, Spielberg directed a romantic tiny film, Amblin’. He brought a record player and a stack of his soundtrack albums into the editing room, and for two weeks, day and night, he would pace the room listening to music while constructing his movie. Amblin’ earned the teen whiz a seven-year contract at Universal—an echo of John’s early career scoring episodic television at Universal—where he directed episodes of TV series like Rod Serling’s Night Gallery. But he always had his heart set on making features.

In 1969, Spielberg read an Associated Press article about a married couple who kidnapped a Texas highway patrolman and led a massive police chase across the state in hopes of getting their children back. He tried to sell the idea as a movie to Universal, but the studio kept him in the salt mines of television. Spielberg directed the pilot and arguably best episode of Columbo, the beloved Peter Falk detective series, and a few months later he finally got his substantial shot to make Duel, based on a tiny story by Twilight Zone alumnus Richard Matheson. The feature-length TV movie was scored by Billy Goldenberg, who wrote “one of the best scores ever written for one of my movies,” Spielberg later said.

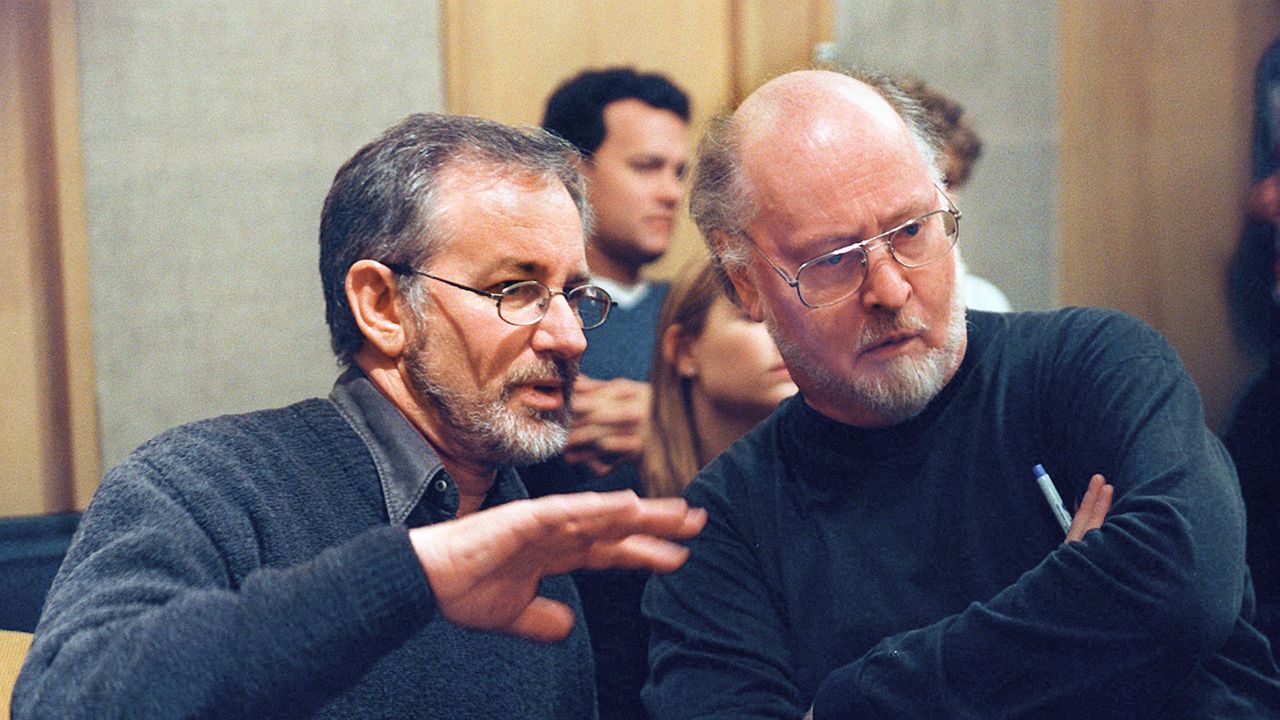

It’s captivating to imagine an alternate universe where it was Spielberg & Goldenberg reigning at the box office. “But everything changed,” Spielberg said, “when I met Johnny.”

Thanks to Duel, which was a hit on TV screens in America and also in European movie houses, Spielberg was finally eligible for the substantial leagues. He had forged several vital relationships with the higher-ups at Universal—including Jennings Lang, who put up the money for Spielberg to develop an outline of the Texas chase story, soon to be called The Sugarland Express. But perhaps Lang’s greatest legacy, or at least the one with the biggest cultural footprint, was setting the lunch date between John Williams and Steven Spielberg (and possibly being the one who picked up the tab).

Lang had known John since the early Revue television days, and he produced several Universal films that John scored; his second wife, actress-singer Monica Lewis, was a close friend of John’s wife, Barbara, from their shared adventures at MGM. Before Spielberg traveled to Texas to film Sugarland, Lang booked a table for the nervous adolescent filmmaker and the veteran composer at a posh Beverly Hills restaurant. Spielberg had just cast Goldie Hawn, and he was determined to have her western adventures scored by the man who had made The Reivers and The Cowboys levitate off the ground. “I had to meet this modern relic from a lost era of film symphonies,” Spielberg said. “I wanted a real Aaron Copland sound for my first movie.”

The film finished shooting in March; John must have screened it in the spring of 1973, and he agreed to score it. Spielberg told him that he wanted a full orchestra with “a colossal string section. But John politely said no—this was for the harmonica and a very small string ensemble.” The resulting score was a lovely but somewhat unremarkable beginning to a partnership that became associated with large-scale adventure, majesty, and awe.

What was evident and auspicious right from the start, though, was Spielberg’s faith in lyricism and unembarrassed sentiment—which John gladly provided. And right from the start, Spielberg was accused of being overly sentimental. Critics found fault in his compassionate characterization of a would-be Bonnie and Clyde. Critics also found Spielberg manipulative. “Everything is underlined,” Stephen Farber sneered in the New York Times. “Spielberg sacrifices narrative logic and character consistency for quick thrills and easy laughs. He has a very crude sense of humor, indicated by his obsession with toilet jokes, and an irrepressible maudlin streak. Early on Spielberg lingers over a shot of the couple’s baby playing with a dog, and after the final tragedy, he moves in for a close-up as a police car drives over a discarded teddy bear. It’s depressing to see a young director who is already so shameless.” But others, like the influential Pauline Kael, saw the debut of a master. “The Sugarland Express is like some of the entertaining studio-factory films of the past (it’s as commercial and shallow and impersonal), yet it has so much eagerness and flash and talent that it just about transforms its scrubby ingredients,” Kael wrote in the New Yorker. “If there is such a thing as a movie sense, Spielberg really has it.”

COMMENTS