The Brothers Quay, identical twins, make marvellous, mystifying films in which eerie stop-motion puppets outnumber the few live performers. These film

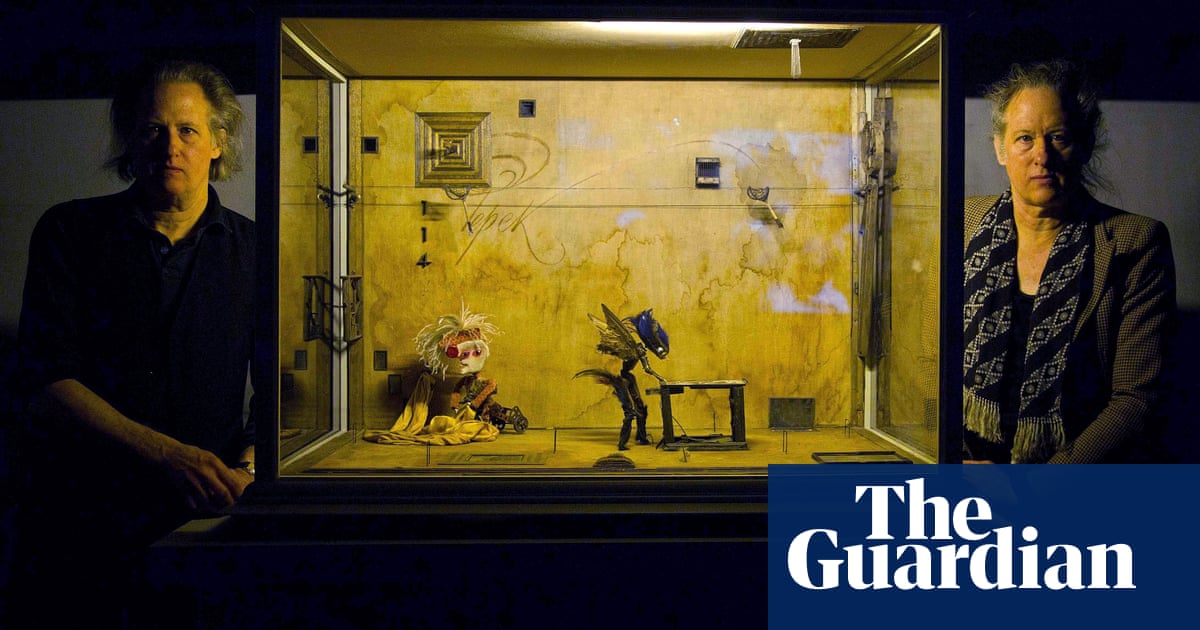

The Brothers Quay, identical twins, make marvellous, mystifying films in which eerie stop-motion puppets outnumber the few live performers. These films might be set in a strange school for servants, or a lecture hall, or a labyrinth, but really they take place in a small desktop universe that runs according to its own alien rules. The brothers hate the idea of having actors voice the puppets and have done so only under duress, once or twice, because it feels so demeaning.

Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass is just their third feature in a 50-year career, after Institute Benjamenta and The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes. Mostly, they make short animations. They also design for the stage, make music videos, and devise site-specific installations such as their Overworlds and Underworlds project in Leeds for the Cultural Olympiad. Film features cost money, take forever, and involve a gaggle of interested parties, which is another word for meddlers. And so they very much doubt they’ll do another. “We’re 77 years old,” they tell me. “No one’s going to fund two old men.”

“What’s this all about?” Christopher Nolan asked us. “Don’t ask these questions,” we said.

I’m delighted that they managed to slip this one under the wire. Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass is unique and opaque, with its own spooky logic. Loosely inspired by the work of the Polish author Bruno Schulz, a perennial Quays touchstone, it’s about a young man, Jozef, who boards a steam train to visit his father at a TB hospital in the Carpathian mountains. So far, so straightforward – except that the film unfolds as seven disconnected scenarios which are reputedly the flashes retained by a detached retina.

We meet in a garden at the Venice film festival, near a clanging church bell that drives the Quays to distraction. Both have wild grey hair and wear billowing cotton blouses. Stephen is discursive and softly spoken; Timothy a shade more pithy and decisive. They insist that they work in perfect harmony. “We don’t really disagree on anything,” they say.

The Quays were raised in Norristown, outside Philadelphia, but never truly felt that they belonged. On their first day at art school, they spotted a display of hand-drawn Polish film posters on the wall and that was that. They were hooked. Eastern European culture has always called to them, and the pungent, oblique writing of Bruno Schulz most of all, because it inhabits a space that animation can speak to.

The brothers have lived in London for decades. Certainly I don’t see much of Philadelphia in their work. “No,” Stephen admits. “But Philadelphia has a very European element. There’s a Ukrainian section and a Polish section and an Italian section, where we lived as children, although we’re not Italian. Our great-grandmother was Silesian. She grew up on the border between Czechoslovakia, Poland and German Silesia. All the languages in one place.”

In any case, they rarely get back to Philadelphia these days. Their father died five years ago. They have a younger brother who is still around. He was vice president of a shipping company and steered a completely different course from them. “He got rich,” Stephen laughs. “We’re still struggling artists.”

On workdays, the Quays sit in their Hackney studio at an eight-by-five table. They build little universes and manipulate tiny figures. Puppets, they feel, are emissaries from the great beyond. They wear their uncanny nature as a badge of pride.

But isn’t every film a conversation between the film-maker and the audience? At some point the Quays, as directors, have to open the door and let people inside. Timothy smiles. “Hmm,” he says. “Reluctantly.”

The Quays’ breakthrough work – probably the one they’re still most identified with – was 1986’s Street of Crocodiles, the 21-minute tale of a liberated marionette (strings cut, roaming wild) that eventually discovers it is not as free as it thought.

The majority of film-makers are governed by the written word. Film was born out of books and theatre, and thereby missed a trick, whereas the Brothers Quay work to music because they’ve found that invariably aids their puppetry.

It’s funny, say the brothers. People constantly demand stories to make sense of their lives. Stories provide a light in the darkness and explain the world around. But the trouble is that any narrative – films, books, journalism, whatever – can only take us so far. In the end, the dark always triumphs, and after that you’re on your own.

Timothy leans in. His smile has turned quite wolfish. “This article,” he says, gesturing at my recorder. “Can we ask that it be written as a non-narrative interview?” I think he’s joking, but then again maybe not. With the Quays, it is sometimes hard to tell.

Conclusion

The Brothers Quay’s unique approach to storytelling, using puppets to create a mystical and disconnected world, sets them apart from other film-makers. Their dedication to their art, despite financial struggles and limited recognition, is inspiring. As they continue to push the boundaries of storytelling, their influence on animation and film as a whole will only grow.

FAQs

Q: What inspired the Brothers Quay to start making puppets?

A: Growing up in Norristown, outside Philadelphia, and being exposed to Eastern European culture and the works of author Bruno Schulz.

Q: What sets their film apart from other animations?

A: Their use of stop-motion puppets to create a surreal and otherworldly world, unlike any other.

Q: Why do the Brothers Quay prefer working with puppets over using live-action actors?

A: Puppets are emissaries from the great beyond and wear their uncanny nature as a badge of pride, allowing for a unique and captivating storytelling experience.

Q: What advice do the Brothers Quay have for aspiring film-makers?

A: To take risks and experiment with unconventional storytelling techniques, and not be afraid to challenge themselves and others.

COMMENTS