This article contains spoilers about the plot of Blue Film, and contains frank discussion of pedophilia.Reed Birney is expecting walkouts. The Tony w

This article contains spoilers about the plot of Blue Film, and contains frank discussion of pedophilia.

Reed Birney is expecting walkouts. The Tony winner, known for his celebrated stage work in The Humans and Casa Valentina as well as recurring roles on House of Cards and American Horror Story, coleads Blue Film, a radical queer drama that was filmed well over a year ago and is finally set for its premiere on Saturday at the Edinburgh International Film Festival. In the movie, Birney plays a part that some—honestly, most—actors of his caliber would consider unfathomably risky. When he read the script, he was “flabbergasted.” But he Zooms before me a proud, if anxious, man, ready for the world to see why he took the leap. “When making the movie was over, I thought, ‘This might’ve been the movie role I’ve waited my whole life to play.’”

Blue Film comes from writer-director Elliot Tuttle, making his feature debut. Tuttle wrote the script while journaling about adolescent sexuality, specifically his private unpacking of a fantasy from when he was in middle school: “I really wanted my history teacher to have sex with me,” he says. Tuttle started writing a movie set in one location, focused on two characters, and propelled by the transgressive. The filmmaker describes initial drafts as a “manifesto” unfurling his many thoughts about sex. Then it became a character drama—then, a kind of psychological thriller rooted in the taboo.

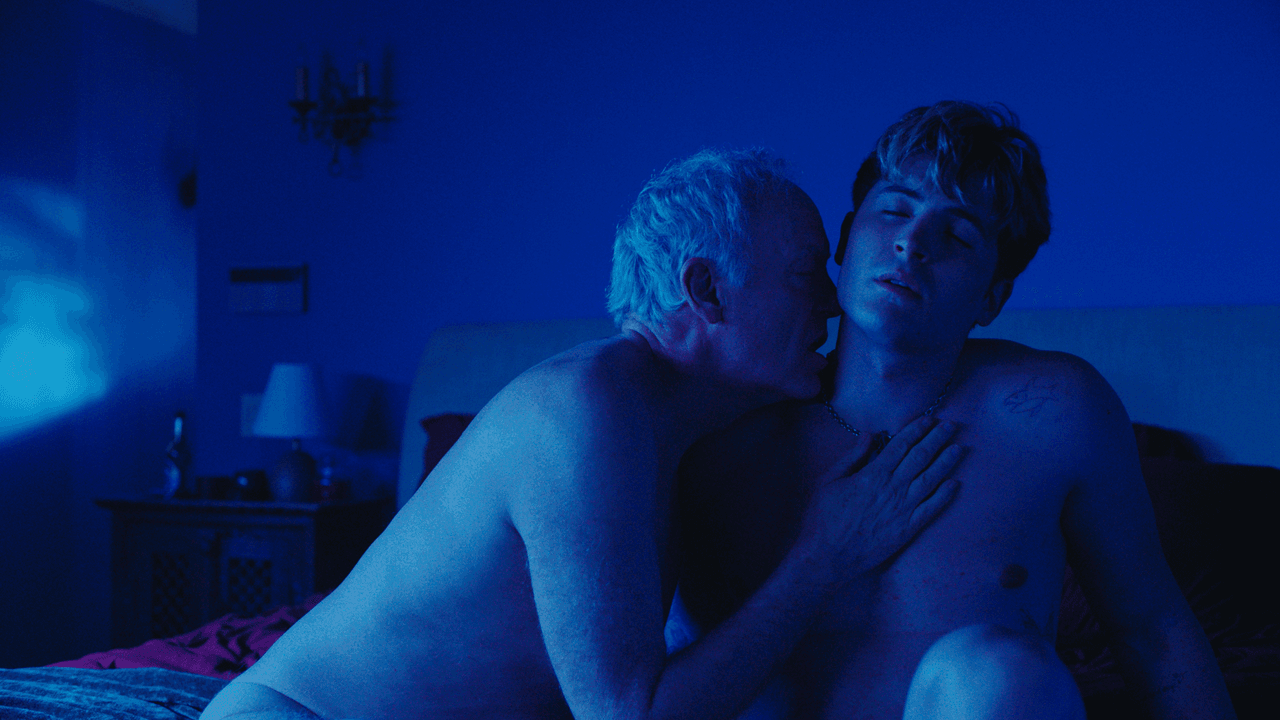

We first meet Aaron Eagle (Kieron Moore), a gay fetish camboy, in the midst of a seductive livestream. He’s hired by an anonymous older man to spend the night at his home—presumably, a straightforward exchange of money for company and sex—only to quickly glean an ulterior motive. The man, played by Birney, interviews Aaron on camera while wearing a ski mask, asking him oddly personal and intimate questions. He seems genuinely curious; Aaron turns deeply uncomfortable. Eventually, Aaron confronts the stranger, removes the mask, and gasps in recognition. “Mr. Grey,” he says quietly. It’s Hank Grey, his aged middle school teacher—the one who was fired for the attempted sexual assault of a 12-year-old student.

“This felt like the logical end point of these fantasies I had as an adolescent, about teachers I fantasized about,” Tuttle tells me. Blue Film then dramatizes a long, complicated conversation between Aaron and Hank that meditates on deviant sexuality and confronts the darkest corners of human desire. Hank admits he was attracted to Aaron when Aaron was a minor. As for why he has brought his aged student back into his life, more than a decade later, he says, “I want to know if I still love you.” Eventually, we watch them explore being physically intimate together.

Blue Film is absorbing, brilliantly acted, intently challenging to stomach, and ethically discomfiting. The movie presents a pedophile as a protagonist while aiming for a certain level of mainstream awareness, requiring its audience to listen to his perspective and grapple with it in good faith. It’s a shocking work of American independent cinema in 2025, considering its subject matter—a topic that’s especially radioactive amid the swirling Epstein files saga. Its insistence on pushing boundaries is completely at odds with an industry terrified of controversy and scrambling to simply stay afloat.

The filmmakers argue that this, actually, is why Blue Film is well-timed—and worthy of consideration. “Trump is ushering in this cultural conservatism that I think forces the queer community and gay tastemakers to really present one view of queerness that is kind of immune to critique…and, to me, pretty boring and not in the tradition of being a queer artist,” Tuttle says. “I’m resentful of what is happening to queer storytellers right now…. People are hungry for something that is not so limited by what’s tasteful.”

“If you feel any sort of feeling towards Hank, it’s because you’ve done something beautiful. You’ve listened to someone that you’ve been told you shouldn’t listen to,” Moore adds. “We don’t humanize him and forgive him. We just speak to his character like he’s a human being, which he is.”

Mark Duplass first met Tuttle as “a high school film fanatic from a small town in Maine.” The indie icon and Blue Film consulting producer has been mentoring the director ever since, for about a decade now. “I’d never met anyone so fully obsessed with the art and craft of independent film,” Duplass tells me via email. “He reminded me a lot of Sean Baker when I met him before we made Tangerine together.” Even so, when Duplass received the script for Blue Film? “It scared the hell out of me.”

Blue Film is produced by Bijan Kazerooni, Will Youmans, Adam Kersh, and Waylon Sall, and was shot on a budget of next to nothing over two intensive weeks. Industry stalwarts like Duplass and Birney lend gravitas to a project that would otherwise be pigeonholed as fringe—and already has been in certain corners. “I felt I was with somebody who had done his homework, and who was smart, and knew what he wanted to do…. He believes that American films are a little coy about sex,” Birney says of Tuttle. “I was not thinking about, ‘Is this a good career move? How’s this going to land?’ I was so happy to do the work.”

Tuttle came of age as a devout fan of European auteurs like Catherine Breillat and Lars von Trier—filmmakers who “are not afraid of what they’re doing, of the truths that they’re trying to represent on screen.” It’s less of a tradition in American movies. Still, Tuttle points out everything from the New Queer Cinema movement to David Lynch’s Eraserhead as examples of an alt-national legacy of courting controversy, and penetrating the zeitgeist, through truly provocative filmmaking.

Tuttle listened to personal stories in crafting the character of Hank, preferring first-person testimony to columns of statistics. “That was majorly helpful to me in at least getting some anecdotal evidence as to the variety of reasons someone might be a pedophile,” he says. The primary guiding delicate for him and Birney was the Sundance-award-winning 2014 documentary Pervert Park, set in the Palace Mobile Park of St. Petersburg, Florida, where more than 100 convicted sex offenders lived at the time of filming. “These people are in a lot of pain—they did not choose to be this way, and they are really, really struggling to make sense of their lives,” Birney says. “I thought, That’s a story that’s worth being told.”

COMMENTS