Some documentaries are straightforward rehashings of a certain event or case. We usually get archival footage interjected by talking head interviews

Some documentaries are straightforward rehashings of a certain event or case. We usually get archival footage interjected by talking head interviews with experts, witnesses, or people close to whatever is being documented. With the growing access to technology used in everyday life, especially in law enforcement, novel elements are being brought into documentary filmmaking, especially in true crime, with the value that police bodycams, personal recordings, and CCTV can offer. Recreations of events can sometimes cheapen the film or series, making it feel like an ‘80s true crime show on cable. Then there are documentaries that blend fact and fiction, using narrative filmmaking techniques to enhance their exploration of real events. That’s where Mati Diop’s Dahomey lands.

The winner of the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlin International Film Festivalblends documentary and cinematic formats to create a poignant meeting point between past and present.

What Is ‘Dahomey’ About?

Dahomey follows the 2021 repatriation of 26 artifacts to the Republic of Benin, formerly known as the Kingdom of Dahomey. Those who saw Viola Davis’ historical epic from 2022, The Woman King, will be familiar with the land and its history. During the French invasion of Dahomey in 1892, thousands of artifacts were stolen from Dahomey, and fast-forward over 100 years later, they were put on display in Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris. After years of calling for the artifacts to be returned to their rightful home, 26 of them, including statues of King Glele and King Béhanzin, are packed up and sent back to Benin.

From the outset, it’s clear that Diop is not interested in a classic documentary style. Rather than opening with 10 minutes of voice-over explaining the Dahomey Wars, French colonization, and the subsequent events that led us to 2021, one title card explains succinctly everything we need to know. From there, Diop melodically moves through the museum, capturing security guards, movers, scientists, and anthropologists going about their jobs. The camera moves around the artifacts to capture them in all their natural beauty, positioned not to glorify them but to simply be in awe of the fact that humans made these, and they are all still standing centuries later.

‘Dahomey’s Narrator Is the Voice of the Artifacts

The most experimental aspect of Dahomey is the interjection of minutes with a black screen and a deep, distorted voice (think “The Voice” from Dune), which is the artifacts’ stream of consciousness, spoken in the Fon language. The screen only shows subtitles against the murky, as if we are in the artifacts’ minds, staring into the abyss as we too are trapped in a wooden crate making our journey home. This is elevated by the muffled sound of nails being drilled in and the featherlight slowly being absorbed, as Diop creates the claustrophobic sense of being trapped. The voice-over of the artifacts tells us their thoughts and feelings on returning home. They wax poetic about not being able to recognize the place they once called home after so many years of being forcibly placed elsewhere.

Related

This Emotional Crime Documentary Was So Compelling, It Changed The Law

A filmmaker’s quest to learn the truth about his friend led to novel protections for at-risk children.

As they arrive back, we see real footage of the people of Benin celebrating their return, with performers and crowds on the street, marking the day as a triumph for the perseverance of their culture and the dismantling of the effects of colonization. While these are joyous, celebratory moments, Diop makes sure to thread through a sense of underlying unease, as the artifact’s voice tells us that they feel “Far removed from the country I saw in my dreams.”

‘Dahomey’s Score Tracks the Film’s Emotional Range

Throughout Dahomey, Diop uses every tool available to her to translate a multitude of emotions at any given time. The score is of particular note, from early scenes with an airy, harp-heavy chime, enhancing the feeble beauty of the statues and the extreme care needed to protect them. Then, the music descends into a synth-heavy tune, creating an ’80s sci-fi feel. It pairs quite well with the voiceover, as it really does sound like Darth Vader. It’s most certainly a choice to have the voice sound so far away from humans, and it definitely alienates and unsettles the audience from the narrator, and distracts from the handsome language being spoken and thoughts being expressed. A more natural voice that would allow audiences to appreciate the vernacular and accent of this region and feel more connected to the narrator probably would’ve made for a more enthralling watch.

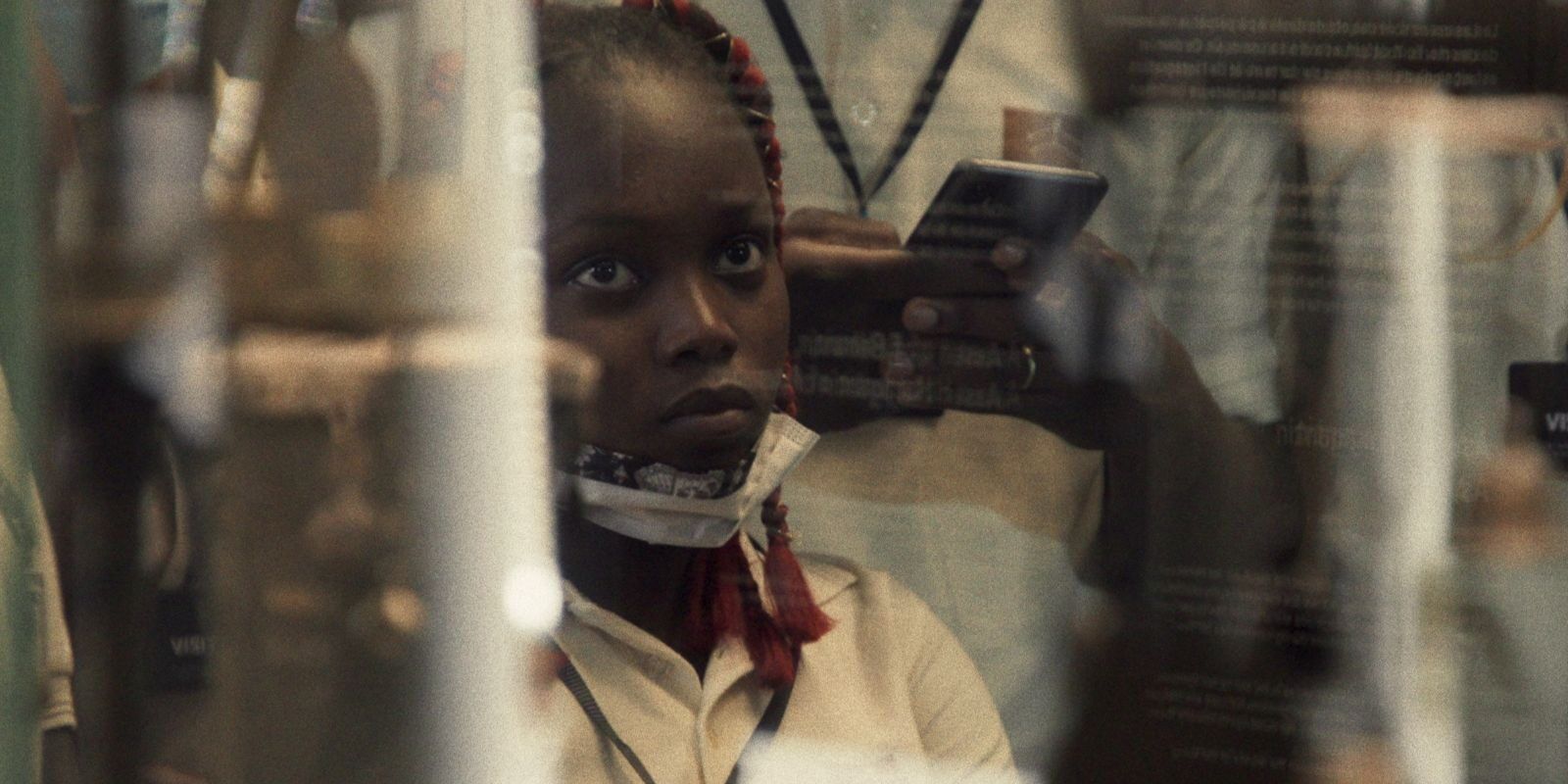

The second half of the film takes a much more naturalistic approach. The camera follows a debate between a group of students from the University of Abomey-Calavi discussing the repatriation of the artifacts. While it certainly is a victory for the country, the students call for all of them to be returned to their homes, as the items sent back to Benin were only 26 of over 7,000 that the Paris museum has in their possession. The way Diop captures these discussions, with a shaky cam that follows the voice of whoever is speaking next rather than neat editing cuts, makes the issues being talked about feel more current as if this conversation is being broadcast live.

What Diop wants to remind the audience of is that while the 2021 repatriation is, of course, a triumph, we (especially the youth) should not become complacent. We should be constantly calling for reparations from colonization, for the West to make right for the atrocities they committed against the East in the past. Choosing to film this part in a less neat, finite way is a great way for Diop to make the documentary and by extension, the issues being discussed, feel more urgent, as if this is all happening in real time.

‘Dahomey’ Confronts the Effects of Colonization

The film calls out the absurd hypocrisy of the colonial powers to continue to benefit from the exhibition of precious cultural objects and parade them as if they’re proud of their history of invading and stealing from other lands. It ends the film on a much more bleak note than you would expect, but there is also something inherently reassuring. By starting the documentary following older French men in control, and ending with the future in the hands of college students whose minds are constantly evolving and are calling for a more just future, the ending of Diop’s film is basically calling out from the screen “We’ve come a long way, and there’s still a lot to go, but the future is in good hands.”

Dahomey may not be for everyone. Unless you’re a history nut or anthropologist, there will be lulls when you find your concentration lagging. However, at a runtime of just over an hour, Diop makes every shot count and packs centuries of history, injustice, and triumph into a dense but colorful documentary.

Dahomey is a ponderous but colorful documentary that takes a non-traditional approach to documenting the centuries-long effects of colonization.

- The score works with each scene to track the emotional range of the film.

- Diop’s camera never feels invasive, and follows a more fluid, relaxed movement.

- The film never focuses too much on a certain subject, allowing space for a plethora of ideas and perspectives.

- The film definitely lulls at times, and may not pique the interest of casual movie fans.

- The voice of the narrator alienates the audience and breaks the flow of the documentary.

- Release Date

- October 25, 2024

- Director

- Mati Diop

- Cast

- Gildas Adannou , Habib Ahandessi , Joséa Guedje , Imelda Batamoussi

- Runtime

- 68 Minutes

- Writers

- Mati Diop

Dahomey screened at the BFI London Film Festival. It arrives in theaters on October 26.

COMMENTS