Welcome to Hollywood–that’s not smog, it’s depression. The entertainment industry currently registers somewhere between slowdown and apocalypse on th

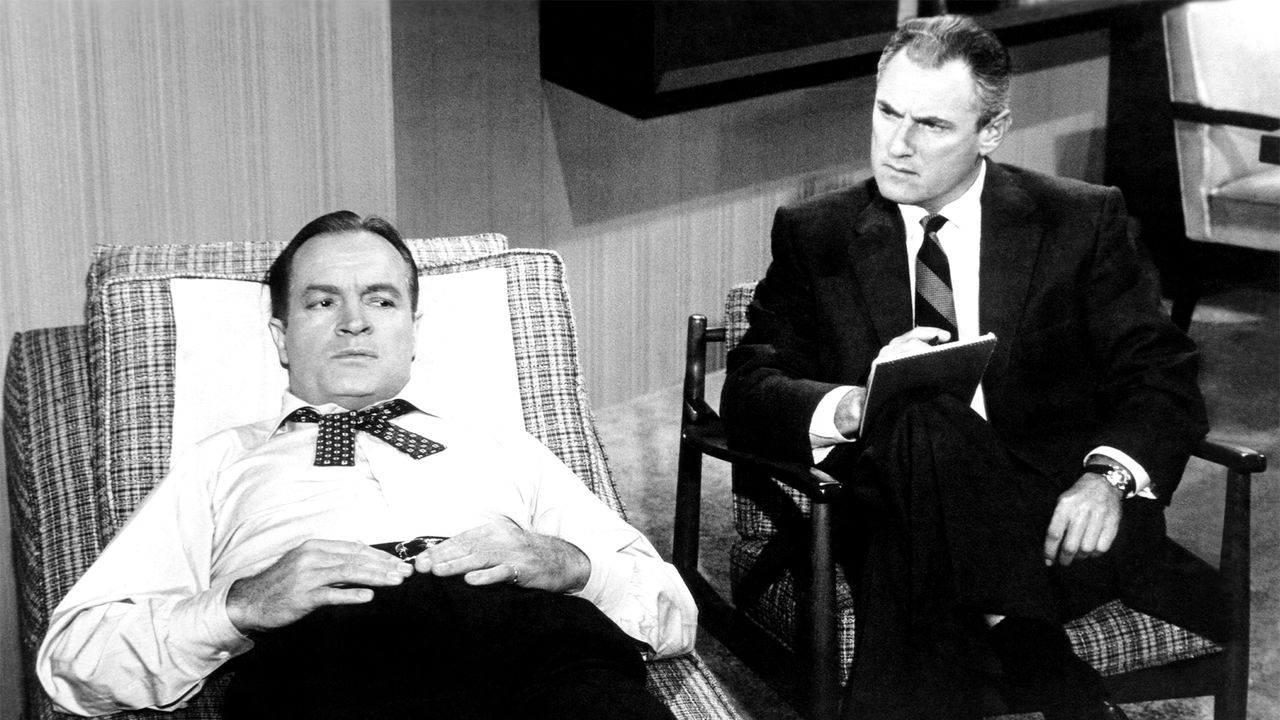

Welcome to Hollywood–that’s not smog, it’s depression. The entertainment industry currently registers somewhere between slowdown and apocalypse on the disaster scale. For many in the business who are either unemployed or terrified that they soon will be, therapists offer support and consolation. That means they serve as a good barometer for the town’s mental health. So what’s the view from the therapist’s chair?

“It feels like the end of days,” says Dennis Palumbo, a psychotherapist with patients predominately in the entertainment industry. “I’ve been doing this for 31 years now, and I’ve never seen this level of despair among creative people in the industry,” he says. “There’s a level of depression and anxiety pretty much unparalleled.”

Film and television production has plunged in Los Angeles. A recent report by the Otis College of Art and Design found that there were 25% fewer entertainment jobs across the board last year compared to post-pandemic 2022, which was not exactly a joyride itself. Palumbo blames it on the triple whammy of COVID, two brutal strikes, and vertical integration, with a handful of enormous conglomerates gobbling so much up. “The business has always been crazy,” he says. “But it used to be that if you had a track record that meant something, if you came off a show, you were pretty certain you’d get on another show. Those days are over. Now you could come off a hit show and you’re still like Sisyphus: your rock is at the bottom of that hill again. It’s very, very depressing for a lot of patients.”

Kara Mayer Robinson, a licensed therapist who also works as an on-set mental health consultant, harks back to the phrase “Stay alive til ’25,” a popular mantra last year for insiders hoping that Hollywood production would ramp back up. “The new normal is that it’s not all going to bounce back,” she says. So one of her key questions for patients is: “What’s your mindset?” Robinson aims to support patients manage the anxiety and fear that may be paralyzing them. “You have to recognize and accept what you can’t control,” she says, “and then you figure out what you can do and take action on that.”

Along with doing whatever they need to do to survive—driving an Uber or waiting tables, in some cases—Robinson encourages patients to keep creating things, even when hardly anyone is buying them. “There’s definitely been a shift where people don’t necessarily trust the studio system and are thinking, Well, maybe we need to be on YouTube,” she says. “But for a lot of people who’ve been doing this for decades, they’re not about to go to plan B. There’s no plan B. This is what they’ve worked their whole life for.”

Ironically, Los Angeles is full of former entertainment people who decided to become…therapists or life coaches. Palumbo, for instance, used to write movies and TV shows (My Favorite Year, Welcome Back, Kotter). Phil Stark wrote for South Park, That ’70s Show, and the movie Dude, Where’s My Car? But when work started drying up after the 2008 strikes, he struggled to figure out what to do next. He eventually zeroed in on grad school and transitioned into his modern life as a therapist, which sees him work with many people languishing in a way he knows well. “The longer you have been doing this career–the longer you’ve been identifying as an editor or a cinematographer or a sitcom writer—the harder it is to imagine yourself changing,” Stark says. “And so it can be a kind of eureka moment when people discover what they previously thought was interesting before they got into the business, like me with psychology.” He sometimes taps his industry expertise to support get to the root of patients’ problems: Why are they feeling crushed by a studio executive’s notes, for instance? “I also might work with somebody who can’t get work and is struggling with depression—sort of sitting with them while that plays out.”

Spending all day listening to people vibrate with panic and misery isn’t always basic—especially if you’ve been in the same situation yourself. Jamie Rose was once a successful actor on network shows like Falcon Crest. By her mid-30s, as acting jobs thinned out, she started seeing Phil Stutz, shrink to the stars. (He’s the subject of Jonah Hill’s 2022 Netflix documentary, Stutz.) Things grew very gloomy for Rose after the 1990 market crash and the 1994 earthquake; the bank foreclosed on her quake-damaged house, and she seriously contemplated suicide. An actor since the age of six, she had no other obvious skills. But she eventually transitioned into teaching and then working as a life coach under Stutz’s tutelage, often taking on patients he referred. One of Rose’s current clients is in tremendous debt, and it brought Rose to tears in a recent session. “Having been at the top in the entertainment industry and then to lose it all—I have firsthand experience with this shit. Been there, lost that!” she says wryly. “But because of that, I get to say to him, ‘You stay alive, no matter what. Even if that means you call me every day between sessions, you need to stay alive.’”

Stark admits that the industry contraction is grim, even though he no longer lives off screenwriting. “It’s like if you watch a video on TikTok about a writer complaining how there’s no work, you’re going to get a lot more videos about that, and pretty soon it’s all you can think about,” he says. “The zeitgeist right now is very negative.” Or as Palumbo puts it, “If you’re not dispirited right now, you’re dissociative.”

It’s especially dire for “below the line” workers (i.e., behind-the-scenes folks), many of whom never had much financial wiggle room even when times were good. “I see people who are at the point where they’re either considering changing careers entirely or they already have, and others who can’t afford to live in Los Angeles anymore,” Robinson tells me. But the panic extends all the way up the ladder. Palumbo says of his agent and manager patients, “They’re pulling their hair out because they’ve never seen it like this. And we tend to be a culture that says, Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. Are you living up to your potential?”

Hollywood executives are not exempt from the epidemic of dread. “It’s difficult to process the enormity of the loss that is going on,” says Karen Jones, who launched her own coaching business after decades in the entertainment business—most recently as EVP and head of communications for HBO and Max. Among her clientele are execs who remain employed but are now doing the work of multiple people in the aftermath of layoffs, as well as those who have been pushed out themselves. For the latter, she says, “It’s really about working through the identity loss that often happens the day that your email shuts down. Those folks—checking emails is the first thing they do when they wake up in the morning, it’s the last thing they do when they go to bed. When that’s gone, there is a tremendous void. Like, who am I now?”

The bottom line, Palumbo says, is learning to cope with uncertainty—something that’s a given in Hollywood. “Do you see uncertainty as a referendum on you, or is it just the shifting winds of the environment?” he asks. “It means you feel bad about who you are, or you realize that you’re going to have to make some very difficult choices.”

Rose, for one, is not sorry that she swapped acting for life coaching. Laughing with relief, she tells me, “I’m so glad I’m doing this and not still waiting for my friggin’ agent to call!”

COMMENTS