In 1976, the TV journalist and aspiring screenwriter David Webb Peoples, under the influence of Martin Scorsese’s and Paul Schrader’s Taxi Driver, wr

In 1976, the TV journalist and aspiring screenwriter David Webb Peoples, under the influence of Martin Scorsese’s and Paul Schrader’s Taxi Driver, wrote a murky Western about a band of prostitutes seeking revenge on the men who’ve disfigured one of their number by posting a bounty, attracting, among others, a famously violent outlaw who has given up his murderous ways for the hardscrabble life of a hog farmer. Peoples named the proposed film, with its vicious themes and language and outbursts of sadism and cold-blooded executions, “The Cut-Whore Killings” (you certainly couldn’t accuse him of sugar-coating). It sat on a shelf. In the coming years, Peoples was involved with some very successful films, receiving writing credits on the atomic bomb documentary The Day After Trinity and the classic sci-noir Blade Runner. His bloody Western was optioned by Francis Coppola, and he was hired to do a rewrite on the medieval fantasy Ladyhawke.

As these things happen, Peoples became a rising star whom producers want to work with, Clint Eastwood among them. In slow 1983, his colleagues at Malpaso Productions got him a copy of “The Cut-Whore Killings” to read as a sample of Peoples’s work, and Clint was stunned by it. He’d had the first look at just about every Western of quality in the past fifteen years, and this was, he later said, easily the best of the bunch. He was deflated when his team told him that it was under option, but when they called Peoples’s representatives to find out if he was available for them, they learned that Coppola’s rights to the material had expired. Clint snatched it right up.

As was the practice at Malpaso, Sonia Chernus, whom Clint had known since before Rawhide and who was still reading scripts for him at age seventy-four, gave it a once-over and typed up her formal response for him. She was deeply unimpressed:

Clint felt differently. He saw something unique and galvanizing, a tale about the steep cost that killing takes on a man. “I’ve done as much as the next person as far as creating mayhem in Westerns,” he said later on, “but what I like about [this one] is that every killing in it has a repercussion.” Considering the violent swath he had cut through the movies, the idea of a protagonist haunted by his misdeeds and yet forced by circumstances to add to them seemed profound. But the story also had an autumnal, valedictory air to it. At the time, he was preparing Pale Rider, and though he loved “The Cut-Whore Killings,” he wasn’t ready to make it. “I put it in a drawer and kind of forgot about it,” he said. “It was like having a little gem, a little cupcake or something that you’re going to savor before you eat it.”

In 1991, on the heels of a string of impoverished box office performances that, save for The Dead Pool, dated back to 1986, he decided the time was right. “One day I took it out and re-read it, and I said, ‘This is what I’m going to do,’” he recalled. In 1990, at the Telluride Film Festival, where he received an honorary tribute, he announced that he would be making a recent Western. Just as he had returned to the genre with Pale Rider to put the brakes on a run of flops, he would saddle up for what was now known as, after the name of the lead character, The William Munny Killings.

A few things needed sorting out before he got underway. He called Peoples at his home in Berkeley and asked for a few scenes to be changed, including the ending, which Clint envisioned as a little more hopeful and tied with a neater bow. He asked Peoples what he thought about casting Morgan Freeman as the hero’s partner. And, said Peoples, he asked, “What did I think of Unforgiven as a title?”

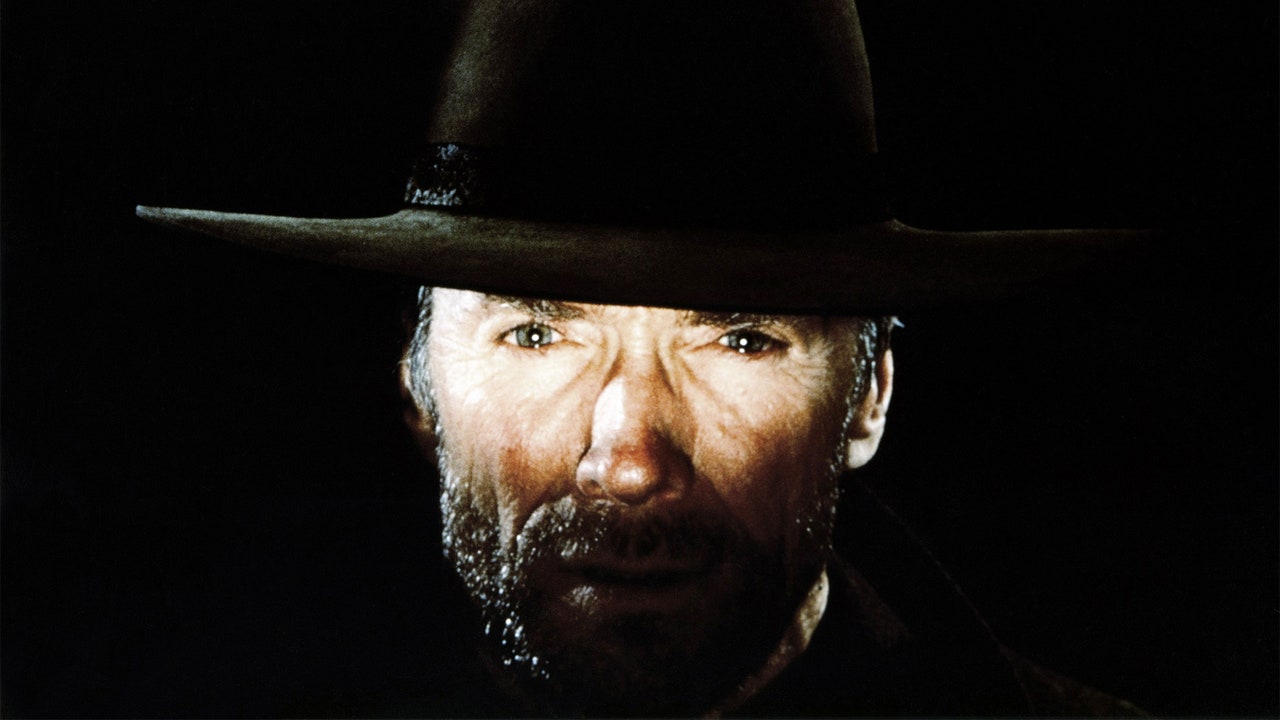

Eastwood, on-set, 1992.© Warner Bros/Everett Collection.

Morgan Freeman, as Clint had indicated, was an elderly Western fan who’d grown up riding horses in Mississippi, and he would often joke to Clint when he bumped into him, “If you need somebody to ride along with you, give a yell.” For the role of a sly, sadistic sheriff trying to keep killers out of his town, Clint had his eye on Gene Hackman, who wasn’t, Clint recalled, interested at first. “He said, ‘Well, I don’t want to do anything with any violence in it.’ . . . I said, ‘Gene, I know exactly where you’re coming from. . . . But I would love to have you look at this because I think there’s a spin on this that’s different. I don’t think this is a tribute to violence.’” Hackman gave it a read and agreed.

For the role of a foppish British gunman who comes to town to collect the bounty, Clint placed a call to Richard Harris, the voluble and bibulous Irish actor. “He was in the Bahamas somewhere,” Clint recalled, “and he says, ‘Who is this calling, anyway?’ And I says, ‘Richard, it’s Eastwood, it’s me.’ And he says, ‘Is this Al?’ He says, ‘Is this Joe?’ He says, ‘You guys are pulling a damn . . .’ And the reason he said that is because he was downstairs in the basement watching High Plains Drifter! And I said . . . ‘I’ll send a script out to you.’ He said, ‘Oh, you don’t need a script. . . . I’ll be there!’”

And in the role of the senior of the group of prostitutes whose search for vengeance leads to the reward that kicks off the story, he cast Frances Fisher, who had just played Lucille Ball in a TV movie and was firmly established in his life as his recent partner. He and Fisher were practically living together in his various homes, where she kept duplicates of essentials, including her running shoes. She still maintained a place near Los Angeles that she shared with her younger brother, but she was Clint’s full-time partner (he gave her a set of golf clubs for Christmas: “Isn’t that romantic?” she cooed). Sondra Locke had been permanently replaced.

COMMENTS