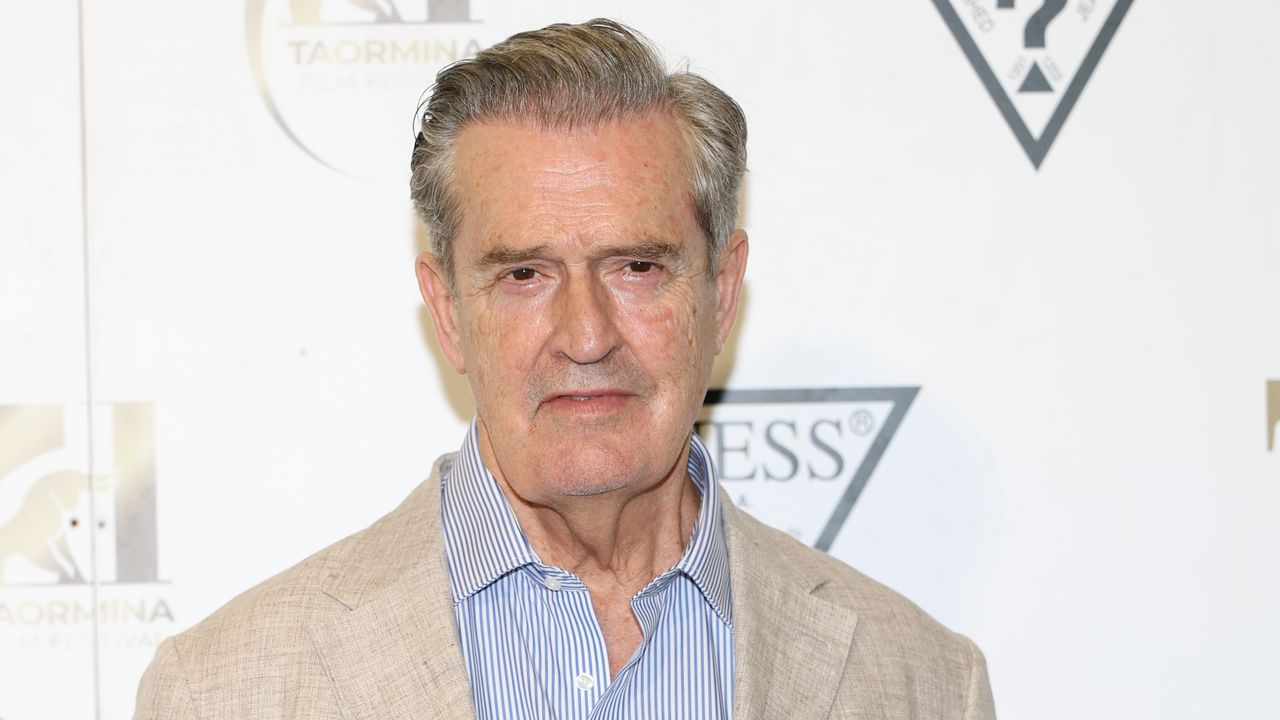

Outspoken. Authentic. Unabashed. Rupert Everett is wont to cut straight to the chase, avoiding unnecessary turns of phrase. The actor speaks his mind

Outspoken. Authentic. Unabashed. Rupert Everett is wont to cut straight to the chase, avoiding unnecessary turns of phrase. The actor speaks his mind—even when the price may be a bit uncomfortable. Throughout his career, he has repeatedly accused the Hollywood system of homophobia, alleging that he’s lost several major roles because of his sexual orientation. Today, things have changed. “I think it’s great that there is less stigma with being gay or lesbian or trans, and you have [more of] an opportunity to work in the cinema,” he said at Marateale, the international film festival held annually in Maratea, Italy. What he doesn’t like is the corollary of that: “If you are a homosexual, you have to play a kind of saint,” said Everett. “You can’t play a character who is a serial killer if you were in a homosexual role in the film, because everyone goes, ‘Oh no, this is such a bad image for homosexuality.’ So that makes it a bit boring. Everyone becomes a kind of cardboard cutout.”

The problem, added Everett, is that in cinema today, “everything is political. Heterosexuality is political. Homosexuality is political. MeToo is political. Race is political. Everything has to be politically correct, and this is a disaster,” said the British actor, born in 1959. “We have a culture of victimization. Everyone is a victim. And I think this is very bad too. When I was young, everyone was a survivor. Now everybody’s a victim. And I think being a victim is very hard work. It looks like it’s fun, but nothing happens once you’re a victim.”

Though Europe has never been richer, Everett continued as his gaze widened further: “We’ve arrived at a kind of standstill point where we’re like Hamlet in Shakespeare”—the man who knows what he must do, but fails to act.

Today’s youth have been raised to believe that anything is possible. Everett thinks this is a mistake: “Young people are educated just to follow a dream, not really to do any work. And that’s completely different to how things were in my era. If you had a dream to be an actor, there was a lot of work you were forced to do. You couldn’t even get a job unless you got a membership at the syndicate. And once you’ve got a membership of the syndicate, you were obliged to work in the provincial theater for two or three years before you were allowed to do anything else. So the work you had to do to follow your dream was much more difficult—and I think it was better also.”

His advice for newborn actors is uncomplicated: Observe their colleagues; read and watch what’s around; notice how people move; and take their eyes off their smartphones. His own career was inspired by Julie Andrews in Mary Poppins, a film that remains his favorite. His path to the stage began in London, then moved to the theater in Glasgow.

Everett is grateful that he had time to learn the craft of acting; in 1984 a play he was performing—Another Country—became a film presented at Cannes. He went on to make several films, including some in Italy with Italian directors. “I wish I’d been a bit older when I worked for Francesco Rosi because I found working for him so difficult,” said Everett. “I found everything so difficult when I was young. I kind of know how to do it now. There’s lots of roles that if I see them again, I think, Oh, I wish I’d known how to do that better.”

In 2018, The Happy Prince was Everett’s first work focused on a historical figure he particularly loves: Oscar Wilde. “For me, he is the Christ of homosexuals,” Everett said in Italian, “because before him there was no talk about this issue. It was all secret. He who was locked in prison for being gay, who lived in poverty his last years, died so that other homosexuals could live: The road to freedom began with Wilde.”

Will Everett direct a second film? Perhaps—but he certainly won’t be in the next season of Emily in Paris: “I was fired,” he said bluntly in English, before switching back to Italian.

“I did a scene in the latest season, and they told me, ‘Next year we’ll speak,’” continues Everett. “I waited for them to call me—but ultimately, it never came, and they just fired me. Show business is always very difficult, from the beginning to the end. When they write the screenplay, they think they want you—but then things change, and they lose your character. I don’t know why,” he says before receiving the festival’s Basilicata International Award. “For me, it was a tragedy. I was in bed for two weeks because I couldn’t get over it.” (Netflix declined to comment on Everett’s version of events.)

Original story in VF Italia.

COMMENTS