Brooke Shields was at a party, drifting off. The host, a petite man with bare feet, was giving her a tour of his wine cellar and she was losing inter

Brooke Shields was at a party, drifting off. The host, a petite man with bare feet, was giving her a tour of his wine cellar and she was losing interest, if she’s being candid – which she is now as a matter of principle, after a lifetime of smiling politely and pretending everything’s fine. Her mind was wandering. They say wine gets better with age, she was thinking, “but isn’t there a moment when it turns to jam? And I said to him, ‘I’m 58 and I’m wondering if…’ I didn’t even get the rest of the sentence out before he said, ‘Oh, I wish you hadn’t told me that.’”

The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

That’s curious, she replied. “I asked him, ‘Did my age make him older?’ I was interested in the psychology of it, that kneejerk reaction.” It was partly, she thinks, her fame – people imprint on a child star, and when they grow up they take it personally. “It felt so indicative of what we do to women, too. And we do the same thing to ourselves – we get caught up, chasing something that’s gone.” It wasn’t the first time somebody had taken offence at the fact she was no longer 15 and she knew it would not be the last, but it was this conversation that inspired her modern book about fame, women and the complexity of ageing. She’s called it, Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed To Get Old.

Today she’s 59, drinking tea (“PG Tips, sorry, I’m obsessed”) in chic spectacles and a cashmere cardigan, talking about the price of beauty. Shields started modelling at 11 months venerable, before she could speak. Her first massive film role, aged 11, was as a girl raised into sex work in Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby. A cover story from a 1977 issue of New York magazine was headlined, “Meet Teri and Brooke Shields: Brooke is 12. She poses nude. Teri is her mother. She thinks it’s swell.” At 14, she starred in Blue Lagoon, playing a teenager coming of age on a deserted island. Talking about the film recently, she said the director wanted “to sell my sexual awakening”.

Both those films propelled her into the public eye, but it felt more like the sight of a gun – Shields was expected to defend her nudity and field debates about child pornography while dealing with her manager mother’s alcoholism, and on TV, and smiling brightly. In 1980, she was the youngest model to appear on the cover of Vogue, and at 16 starred in a series of controversial Calvin Klein ads, her career quickly becoming defined by a sexuality that she and her public are still trying to unpick. If this career had been unrolling today, the internet would have toppled beneath the weight of discourse, of heated takes, op-eds, cancellations, horror and glee.

A recent documentary series (also called Pretty Baby) explored the way Shields’s experiences reflected some of the dread at the heart of beauty culture – the ways, for example, we exploit newborn women to sell a product and how, in that process, women become a product themselves. One clip sees Shields dissociating as she meets the first toy doll made in her image. In another she talks, for the first time, about how a Hollywood executive raped her in her 20s. Elsewhere are scenes of pointed torture – shooting Endless Love at 16, director Franco Zeffirelli sharply twisted her toe so her look of pain might read on camera as orgasmic ecstasy. She would “zoom out” at moments like this, she said. “You instantly become a vapour of yourself.”

Most people don’t get to watch a film of their lives, Shields acknowledges, leaning in with her tea, but says perhaps they should, we all should, in order to come to terms with our own inevitably complicated pasts and see them laid out, well-lit. Watching the documentary Shields found herself horribly moved, she says quietly, by “the nuance of mothers and daughters, the nuances of sexuality, the power in sexuality and how it is used. And it’s one thing to say ‘They were victimised by it’, but it paid our bills! We knew what we were doing. So I think that that was an important piece for me to see.” She talks merrily but deliberately and insists, repeatedly, that while most will see the film as a cautionary tale, hers is not a “sob story”, that she should not be seen as a victim. “Why? Because to me that signifies inaction. I don’t have respect for that. Shit happens and it sucks, but what are you going to do about it? Instead of this ‘poor me’, it’s like OK, now what? Cry about it, feel mad about it, hurt, do whatever, but then get on with it.” She raises her chin and twists a gold ring on her finger – the ring is printed with a diminutive smiley face. “I’m not trying to prove anything. I just don’t like indulging it, I think. I’ve seen too many people do that and I find it… distasteful.”

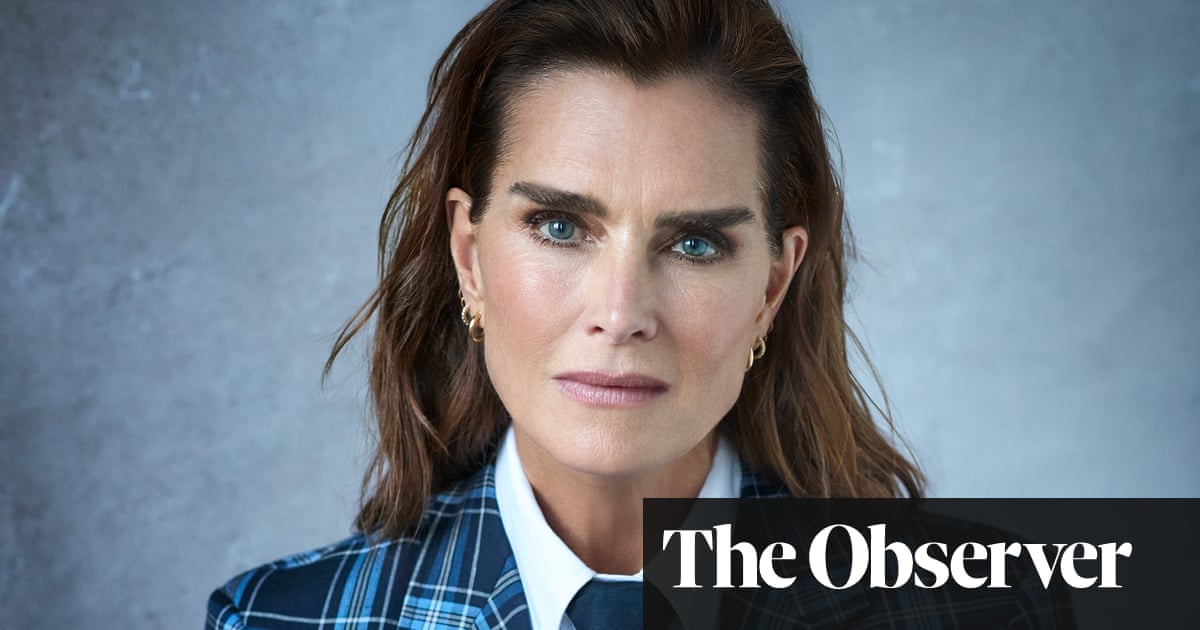

‘Cry about it, feel mad, hurt, do whatever, but then get on with it’: Brooke Shields wears shirt, tie and suit, all by thombrowne.com. Photograph: Richard Phibbs/The Observer

Recently, Shields was telling her therapist about the one question everyone asks her. It’s a question I had scrawled in the margins of the book, it’s one my editor emailed, too; it’s one that’s difficult to avoid when you dip back into the shallows of her history, then see her today, a happily married New York mum with hair like polished teak. It’s: how did you turn out so normal? She’d always answered the question with a bemused sort of gratefulness, talking about her Princeton education, her focus on keeping her mother alive, how her mother’s addiction issues meant she was never attracted to drugs, the way Shields’s beauty had been positioned as a job, with little relation to self-worth, but this time the therapist said: “Stop! When are you going to allow yourself to see that your survival is a result of your individual character?”

Shields’s eyes widen as she explains. “She’d said it in different ways for probably decades, but I just could never hear it. It was such a weight off my chest, it was almost as simple as: I am a good person. I am talented.” She choked up. “It gave me a lightness.” It changed her. “I thought, ‘Yeah, I’m going to walk into rooms now, owning all of my history, owning my experience.’ You think, ‘God, this could have gone a whole different way.’ But I’m glad it didn’t. And I think I fought for it,” for normality, for respect, “whether I knew it or not.” She remembers one TV chatshow in the 80s where the interviewer kept asking her the same question, “And I said, ‘Excuse me, but I keep answering you and I don’t have another answer. This is my only truth.’ I said, ‘I think you might want a different answer, but I don’t have one.’ And I was just struck that I had the balls to do that!”

How does she feel now, watching that little girl on film? “I don’t pity her. I feel like a lot was unfortunate, but the way I lived through it and weathered it, I think formed my character, a character that I started very quickly to learn to rely on.” Those interviews quickly changed the way she felt about adults. “It was like, ‘Wow, you guys made me lose respect for you at such an early age,’ the effect of which was, ‘I didn’t have to worry about getting cut by you.’” As she got older, “Whenever I started to feel broken down by the fatigue or the vitriol or the judgment and then later with social media, I looked at that little girl and I thought, she was going to survive no matter what.” Instead of adversity “building character”, she says, “it reveals character.”

As Shields approaches 60, she’s become more focused, she says, on the pursuit of her own agency. Today the barriers are no longer her youth or male directors, or the publishers of her first book in 1985 (who edited it to become a thesis about virginity and legwarmers), but she still finds her voice being silenced, sometimes because of her age, sometimes her fame (as in recent investment meetings for her modern beauty brand), sometimes her gender. She smiles, shakes out her hair and tells me a story.

Eight years after she’d had her daughters, her gynaecologist recommended Shields have a labial reduction procedure. “She said, ‘If you’re uncomfortable, there’s a fix.’” Looking quickly at me to check, perhaps, for judgment, she continues. She found the best plastic surgeon in LA, and when she went back for the checkup, “He was like, ‘Yeah, it took a long time,’ and then he kind of gave me a little wink. And he goes, ‘because I tightened it all up a little bit.’” He’d performed an unsolicited vaginal rejuvenation when she was anaesthetised. The story – like many from her past – has its own particular fable-like horror. “I was gobsmacked, as you might say. Speechless. He was acting like he had done me a favour of some kind, but I didn’t ask for that, I didn’t need that. I walked out of there stunned.” She slowly shakes her head. Her ability to “become a vapour” continues perhaps, to protect her. “The audacity and the crime!” She considered suing the doctor, but eventually decided against it, mainly because “I didn’t particularly want talk of my lady parts, once again, on the front page of every paper.” All she could think (she writes) was, “Why can’t everybody just leave my vagina alone?”

She pauses for a second, sipping her tea. “One good thing that came out of it was that it made me feel more at one with women. When I was in the hospital with a broken femur, this brilliant surgeon saw me and said, ‘Oh, dear God. Famous people get the worst treatment.’ He said, ‘Doctors either want to show off or they want to prove to you they don’t care who you are.’ And neither of those are healthy or productive. But I think this experience made me feel more unified with women, realising – that stuff like this is happening all the time.”

Watching the documentary helped her think more deeply about her relationship to fame. She’d already realised “that I needed to make something more out of this… infamy? I wasn’t going to be able to disappear and be anonymous, so what was I going to do about it? Was I going to become a hermit? Or get angry and shave my head or punch a photographer?” She knows that feeling, when “you are like a cornered animal and then rage happens and you want to do something self-destructive,” but has never given into it. Instead, “I thought, ‘My God, I need to diversify here, because I’m going to start resenting being recognised and having no art to show for it.’” So last year she accepted an invitation to perform a one-woman show at a Manhattan supper club (a chance for her ‘voice to be heard’, and accompanied by piano too!), and she sang a song called Fame is Weird. Gazing up towards the window, teacup in hand, she recites the lyrics in a deadpan drawl.

“I burst on the scene in the 80s. Things were really different back then. Not as many people were famous and I was four of them out of 10.” She grins. That fame continued throughout the 90s, too, when Michael Jackson claimed they were dating, and through her tumultuous first marriage to Andre Agassi. “Believe me, I’m grateful for all of it. Still, I’ve lived through some really weird shit, fame is weird when you’re a preteen. They write about your period in People magazine. You see your jeans on display at the Met and Donald Trump asks you out on his jet. Wayne Newton bought me a pony. Oddly, Peter Fonda did, too… How have I not gone off the rails? Fame is weird. It can mess with your head. You get, ‘My God, I love you and I thought you were dead!’”

She was 22 when she got the call from Trump. He’d just finalised a divorce and had tracked her down in an anonymous hotel room because, “he said, ‘You and I should date.’” And I said, ‘Excuse me?’ And he said, ‘You’re the most pretty woman in the world and I’m the world’s richest man and the people will love it.’” She grimaces and laughs, and then we’re off, revisiting the most showbiz moments of her half-century career. “I mean, Frank Sinatra was a big one for me. The more whisky he drank, the more adamant he became about protecting me. I was 16 or something and he said, ‘You know what? You’re a nice kid. You’re a good kid.’ Then they brought him this full bottle of whisky and he’s drinking and he’s like, ‘No, no, seriously, You’re a good one. Don’t change.’ OK. And tThen it was a hand on the shoulder. ‘I’m not kidding you, kiddo. Get out. Don’t let this business destroy you.’ By the end of the bottle, he had me practically in a headlock. He’s like, “Anybody fucks with you, I’ll kill them.’” She was able to see the ridiculousness of fame even then, she says, if not exactly enjoy it. “I would write in my diary, ‘No one would believe this,’ before a story about Elizabeth Taylor asking me to score the bottoms of her shoes so she didn’t slip.” Once (she told the sold-out Manhattan club) she pre-chewed Taylor’s gum. When she met Bette Davis at the Oscars she said, “Hi, I’m Brooke Shields,” to which Davis replied, drily, “Yes, you are.” When Ben Stiller took her to Madonna’s house, Madonna sneered, “Oh, you.”

After divorcing Andre Agassi, in 2001 Shields married screenwriter Chris Henchy and two years later, after giving birth to their first daughter, she wrote a book about “the fog” of postpartum depression she’d just emerged from. She was unprepared for the uproar that would follow, largely due to Tom Cruise’s claims she was spreading misinformation about the exploit of antidepressants. Once again her life became a press scandal. In the past she’d been encouraged to smile and stay serene, and though her publicist advised her not to respond, she ignored them and published a column in the New York Times that refuted Cruise’s claims that she should have used “vitamins and exercise” to combat her depression. It was a turning point for her – she testified in front of Congress and helped pass a law in New Jersey requiring doctors to educate expectant mothers about PPD and to screen them at postpartum visits. She was applauded, but “These external outcomes,” she writes, “were secondary to the realisation I am my own best spokesperson.” She narrates her evolution towards empowerment carefully, mindful of veering into self-help platitudes, sometimes succeeding.

“I was always afraid of thinking I was beautiful,” she says today. “I couldn’t gaze at myself with reverence because it felt like those fairytales, where somebody looks too long in the mirror.” Then, as age came, and as her appearance changed, “I felt like I was disappointing everyone. I divorced myself from it for a very long time and just nurtured other parts of my life that I could pay attention to.”

First that was her comedy career, then IVF, then parenting, bringing up her daughters Rowan and Grier, and revelling in their beauty. “They spend so much time on themselves and they encourage me to do it. So, it’s sort of transferred on to me this new joy, all of us standing in the mirror curling our hair, together.” Some of the final scenes in the Pretty Baby documentary were intended as mute footage of the whole family to be used during the credits. But what unfolded, as they crowded around the kitchen table, was a conversation with Shields’s daughters, then 19 and 16, about her early career, and consent, and exploitation.

“I’ve seen Pretty Baby edits on TikTok and it makes me not want to watch it,” says Grier, referencing the 1978 film. “It’s about something that’s not OK now. Right?” Their kitchen appears to vibrate as, in the moment, the parenting role switches, and Shields stumbles as she tries to explain. And they tell her, with a careful tenderness, “Everything is different now.”

Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed To Get Old: Thoughts on Ageing as a Woman by Brooke Shields is published by Piatkus at £25. Buy it for £22.50 at guardianbookshop.com

Stylist Jason Rembert; makeup by Tiffany Leigh Patton at Paradis agency using hourglasscosmetics.co.uk and cremedelamer.com; hair by Sky Kim for The Only Agency using randco.com and ghdhair.com; photographer’s assistant Chika Kobari

COMMENTS