The Cairo Film Festival, which began its 45th session the day before yesterday, is holding a special symposium on

The Cairo Film Festival, which began its 45th session the day before yesterday, is holding a special symposium on director and producer Mustafa Akkad, who passed away on days like these, the victim of a terrorist attack in Amman 19 years ago.

The director of “The Message,” about the origins of Islam, and “Omar Al-Mukhtar,” about a fighter for his country’s independence, were, and still are, the two largest Arab-international productions known to cinema.

The occasion deserves attention, firstly, to remind us of an Arab director who broke through the mute wall regarding the history of Arabs and Islam in his films “The Message” (1976) and “Lion of the Desert” (1980). Secondly, because he is the only Arab director who succeeded in transferring Arab historical events to the screen with a 70 mm Panavision system, as well as the films of the British David Lean, most notably “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962), which brought together international actors (Anthony Quinn, Peter O’Toole, Alec Gaines, and Jack Hawkins, Claude Rains) along with Omar Sharif and Jamil Rateb from Egypt.

After his special show at the Cairo Festival, he will perform in many Arab shows in Jeddah, Doha, Dubai, and Cairo, and efforts are underway to expand the scope Arab and international.

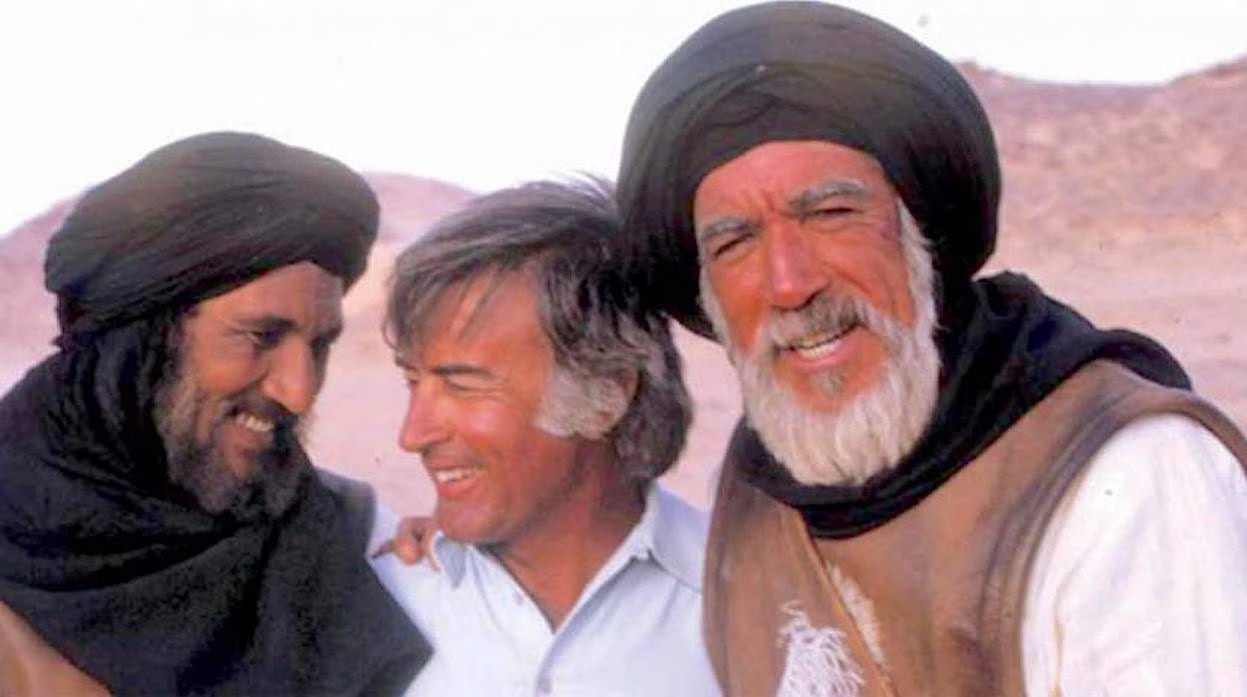

Mustafa Al-Akkad with Abdullah Ghaith and Anthony Quinn during the filming of “The Message” (Falcon International)

Experience and talents

It was not effortless for the actors who appeared in Al-Akkad’s two films to hand over the amounts of their profession at that time to an unknown Arab director. All he had to offer – in addition to his ambition – was that he worked as a production and directing assistant in some American television stations. But Akkad quickly won trust, with the two topics raised in these two films likely to be an additional attraction. The first revolved around a message (about the Islamic religion) that the West did not recognize in a previous film, but rather remained deposited in academic studies and books. The second is a Libyan revolution against Italian colonialism, formulated with care and balance by Akkad. The quality of presentation was also taken into account.

“The Message” was published in two separate versions, one in Arabic or representing some of the best Egyptian, Maghreb, Syrian and Lebanese expertise, and one in English. Both of them were the success of a well-thought-out work despite the difficulty of implementing it.

The second film told that there were other revolutions that occurred during the occupation of parts of the Arab world, and that mass death was similar to others around the world.

No sooner had Anthony Quinn and Erin Pappas signed their contract than others like Michael Ansara, Damien Thoms and Michael Forrest came running.

Later, when “The Message” went out to international shows that included many Arab and Western countries, it became easier to attract other stars, led, once again, by Anthony Quinn in the role of Omar Mukhtar. Then Quinn said to this critic in an interview: “I knew nothing about Arab history. Al-Akkad opened my eyes to this unknown history with his two films, with insight, and how to produce an appropriate major historical film. “As an actor, I see that everything was in its right place.”

Unrewarded attempts

We cannot ignore the fact that Arab historical-religious films had a previous presence in “The Message.” We are talking about “Wa Islamah” by the American Andrew Marton, which was produced in Egypt in 1961 and starred Lubna Abdel Aziz (in the role of Shajarat al-Durr), Ahmed Mazhar, Rushdi Abaza, Youssef Wehbe, Mahmoud El-Meligy, Carioca, Imad Hamdy, and Farid Shawqi.

Ten years before him, Ibrahim Ezz El-Din achieved “the emergence of Islam” with restricted capabilities, along with Kuka, Imad Hamdi, Ahmed Mazhar, and Siraj Mounir, among others. Then, 10 years after the appearance of “Wa Islamah,” Salah Abu Saif completed “The Dawn of Islam.” Which benefited from Abu Saif’s experience, even though in the end it remained a local production for the Arab market.

There is also “Al-Nasser Saladin” by Youssef Shaheen (1963), in which the director employed the best of his energies and crew, which contributed, in addition to his well-known name, to this film joining the rest of what was mentioned in an Arab world that was looking forward to such promotional films for their topics with great interest that suits everyone. That is the effort that these works witnessed.

Iraqi cinema realized that there was a way to produce productions that aspire to internationality, with scales and production systems that Akkad proved possible. In this regard, director Salah Abu Saif created “Al-Qadisiyah” in 1981 at the request of the government during the Iran-Iraq war. The film was highly produced as it was intended to be, faint in its technical aspects, and propaganda in the rest.

The Iraqi Cinema Foundation, which produced it, turned to another Egyptian director, Tawfiq Saleh, in 1980, and insisted that he make “The Long Days,” which went back to a more recent history to narrate part of the biography of the delayed Saddam Hussein’s life.

In 1983, the Iraqi Muhammad Shukri Jamil wrote “The Great Question” (1983), about the Iraqis’ revolution against the British occupation. The director brought in director of photography Jack Hildyard, who had worked with Akkad on his two films, and actor Oliver Reed, who had co-starred in “Desert Lion,” but these films remained restricted in circulation and did not exceed the limits of screening in some Arab countries.

What restricted the spread of these films internationally was the dilemma of many Arab productions at the time, which was the dominance of “The Issue” over artistic treatment, in addition to the fact that Al-Aqqad understood and digested the rules of international productions more than anyone else.

COMMENTS