Disclaimer was designed to keep viewers spinning until they aren’t sure what to believe, or who is right or wrong. The series, from Oscar-winning fil

Disclaimer was designed to keep viewers spinning until they aren’t sure what to believe, or who is right or wrong. The series, from Oscar-winning filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón, begins with audiences feeling unmitigated scorn for Cate Blanchett’s character, who finds humiliating secrets from her past revealed in a mysterious self-published novel. As the show progresses, Cuarón gradually makes viewers begin to question their assumptions about her—and the veracity of this supposedly truth-telling book. By the time the revenge plot by Kevin Kline’s embittered venerable man reaches its crushing conclusion, Disclaimer’s audience veers back in the other direction.

Fair warning, spoilers ahead: Blanchett was the wronged party (brutally so), and not the perpetrator. No one listened. Half-truths and assumptions led the characters to lash out at each other. Judgment and recrimination overpowered fairness. But now that the finale has aired, Cuarón points out that the viewers themselves were never overtly misled—at least not by him.

For anyone who feels disoriented or distraught by a world that makes no sense, Disclaimer now serves as a moral compass. When suspicions run high, anger clouds every view, and the impulse is a rush to judgment, Cuarón says it’s significant to remain clear-eyed, careful, and true. Here, he explains the ending of Disclaimer, and how self-righteousness often only adds more misdeeds to an avalanche of wrongs.

Vanity Fair: What was your philosophy about guiding the audience? How did you want their beliefs to evolve from the beginning to the middle and finally the end of Disclaimer?

Alfonso Cuarón: Well, the factor underneath it all was something that Cate and I worked on very closely and very carefully: not to mislead audiences. If you watch the whole thing for a second time, you realize that everything is out in the open.

So, many of the terrible things we believe at first aren’t confirmed in the story. There’s accusation, and insinuation, and we’re making leaps…

We saw that as an opportunity to thematically explore the impact of how we perceive our narratives and how we also employ narratives. The story is told through several narratives with voiceover, and also there is the narrative of the novel. And all of those are in complete conflict. Then there’s a narrative that is even more significant—that is the narrative of the audience with his or her own judgments and assumptions.

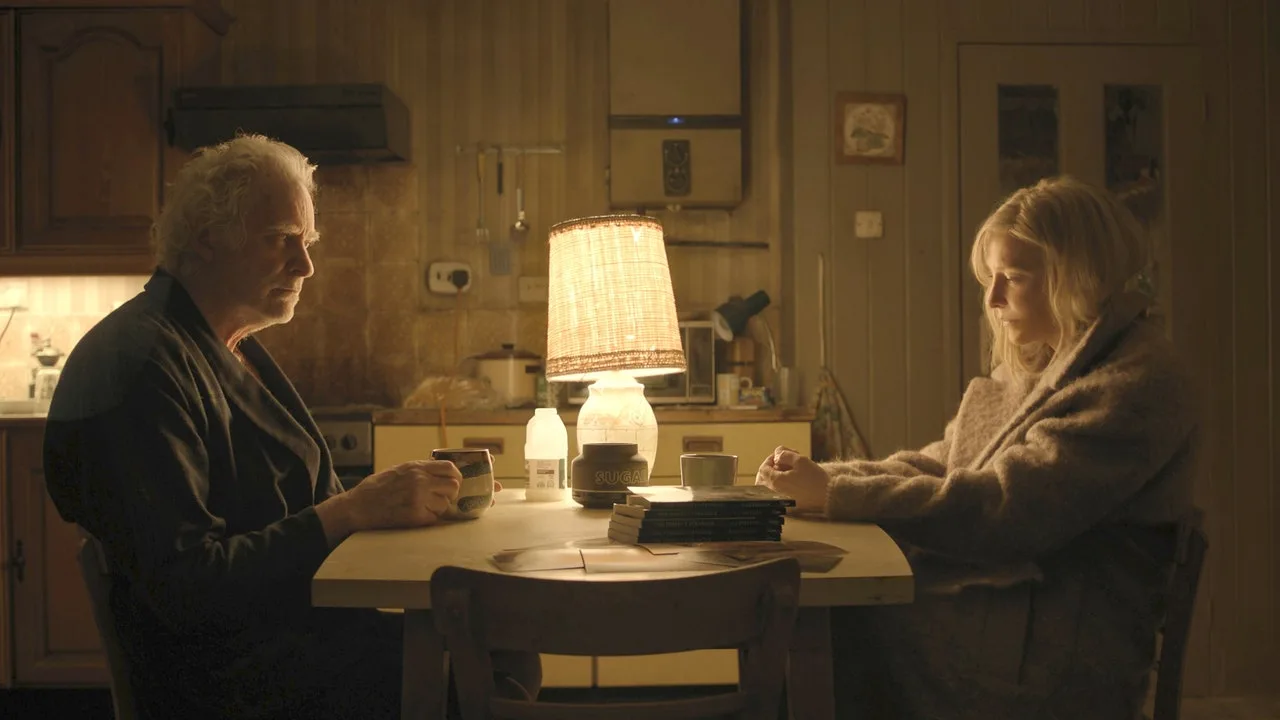

Kevin Kline’s character, Stephen Brigstocke, launched his revenge plot against Cate’s character because he blamed her for the death of his son. It turns out that the nude pictures he found of her were not signs of a romantic relationship, as his overdue wife assumed, but were instead evidence of a horrific crime the adolescent man committed against Cate.

It’s the only moment of certainty that he probably had in his life, and he caused so much pain.

It ends with Kline burning his poison-pen novel about her, all of his son’s belongings, and even his wife’s sweater and his wedding ring. What did you feel you were saying about the nature of revenge and those consumed by it?

COMMENTS