The adventure of translating a French comic book into Arabic was a challenge that required a small miracle. The project was undertaken by Moaz Ziadi,

The adventure of translating a French comic book into Arabic was a challenge that required a small miracle. The project was undertaken by Moaz Ziadi, a Moroccan engineer, and his publisher, Leila Chaouni, a human rights defender who runs a publishing house in Casablanca.

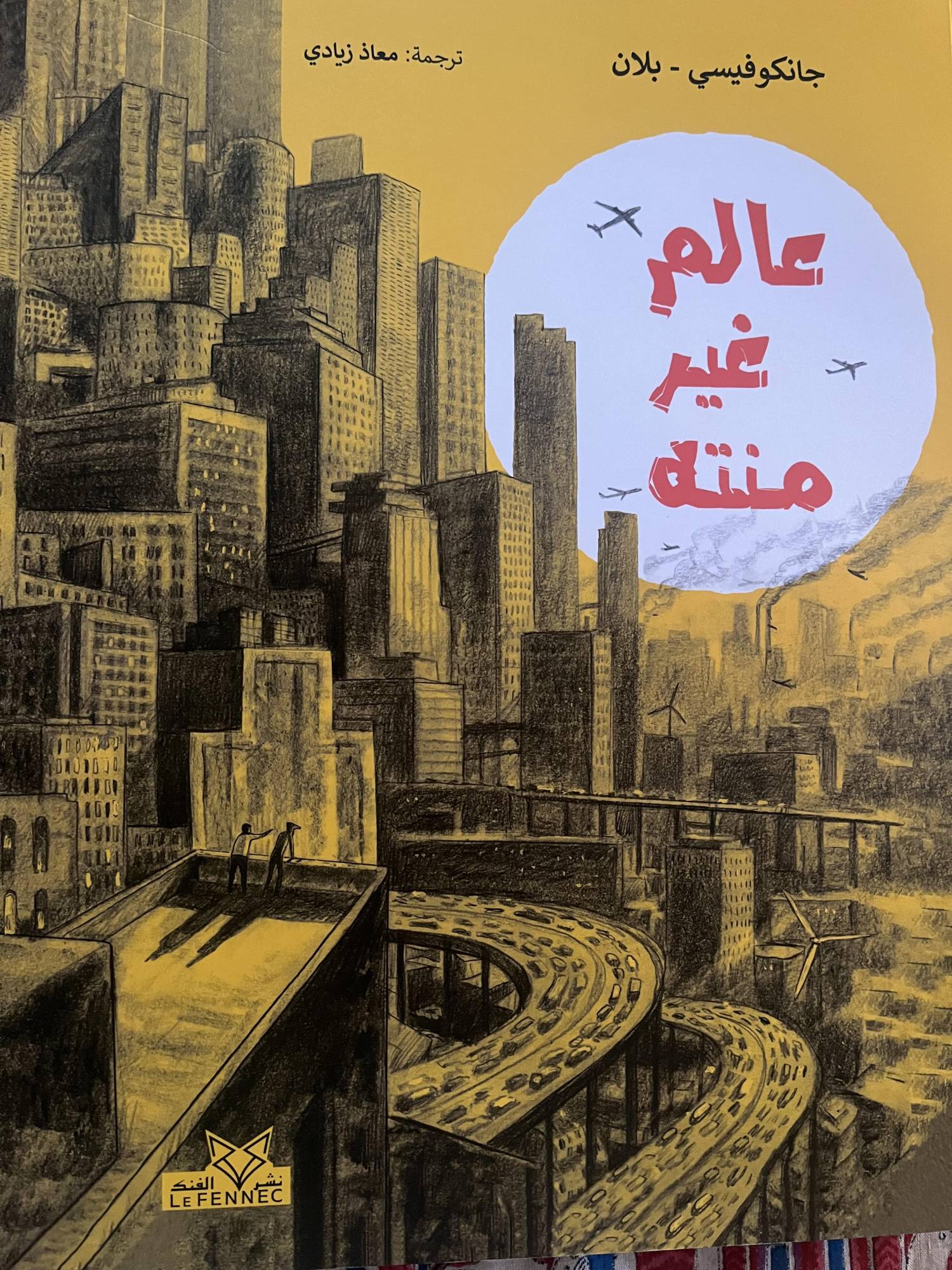

The book, “The Infinite World,” is a joint work between its author, Jean-Marc Jancovici, an engineer and university professor, and the artist Christophe Blanc. The comic book combines science and literature, explaining the problems of global warming in a style of dialogues and comics. The French edition of the book achieved amazing popularity, and its success encouraged Moaz to translate it into Arabic.

Moaz Ziadi discovered the world of Jancovici and Blanc through his work as an engineer. He was impressed by the way the writer and illustrator chose to convey the idea, using the comics technique to simplify the scenario and make it accessible to a wide range of readers. The book’s success was not limited to France; it was also popular in institutes and institutions, which purchased it to raise awareness among students and employees about energy resources and climate change.

Moaz’s own experience with comics began in his childhood, when his mother used to read them to him before bedtime. He continued to read comics throughout his education, including Arabic and French books and magazines. His love for comics and his knowledge of the Arabic language and literature enabled him to create simple dialogues that are accessible to a wide range of readers.

As an engineer, Moaz felt a sense of responsibility to contribute to the solution of global warming. He believed that literature plays a major role in communicating scientific ideas and helping science discover projects to achieve in the future. He also believed that the book’s size and illustrations were not obstacles to translation, and that the biggest challenge was finding a publisher who would accept the risk of buying the rights and bearing the cost of translation and illustration.

Moaz’s translation of the book was not an easy task. He had to find a way to simplify the language of scientific dialogues while maintaining the accuracy of the information. He tried to avoid using footnotes and instead used simple language and illustrations to make the book accessible to a wide range of readers. The book is intended for everyone, from children to adults, and is a family read and a reference in schools and universities.

Conclusion:

The translation of “The Infinite World” into Arabic is a significant achievement that aims to raise awareness about global warming and climate change. The book’s success in France and its potential to reach a wide range of readers in the Arab world make it an important tool for promoting sustainability and environmental responsibility.

FAQs:

* How did you get to know the world of Jancovici and Blanc?

At first, I knew the writer Jancovici from afar, since I worked with his engineering consulting firm on projects assigned to the companies I work for. But I was unaware of the literary side of his personality. This side was skillfully highlighted by the French painter Christophe Blanc.

* Why did this book interest thousands of readers?

Upon its release, this comic book caused a huge stir in France and was very popular with young people. Some institutes and institutions even purchased it and provided it to their students and employees to raise their awareness of the problem of energy resources and climate change. For my part, I liked the way the writer and illustrator chose to convey the idea by relying on the comics technique. They succeeded in simplifying the scenario through a dialogue between two characters: the writer who plays the role of the skilled expert, then the illustrator who plays the role of the naive recipient.

* How did you find the book?

I got to know it in the context of a debate organized by the company I work for. They gave copies of it to all the department heads. I finished reading it in one sitting, and I found in my hands a scientific work that gathered many cognitive concepts in one volume. Blanc succeeded in putting the appropriate graphic imprint for the content with great skill, which gave the book a special flavor.

* How did you come up with the idea of translating it into Arabic?

I read in the newspapers about the book being translated into German and the author welcoming the version, since the book criticizes German energy policy. I thought about an Arabic version and contacted Jankovici to pitch him the idea, especially since most of the fossil fuels used globally are produced in Arab countries, and it has become necessary in light of the issue of global warming and the beginning of those countries shifting their economies to new, more sustainable horizons.

* Isn’t it strange for an engineer to have the experience of translation?

It was certainly the engineer’s perspective that brought interest to the subject, and also because I was recently, in the context of my professional work, working on a sustainable development plan for the design and construction of shopping malls in Europe. When I started looking at how these projects were increasing greenhouse gas emissions, I felt the responsibility that an engineer must have, whose job is not limited to finding scientific solutions for the projects he completes, but they must also be environmentally friendly.

* I see that you consider this book to be a literary book, even though it deals with a scientific issue?

I believe that literature plays a major role in communicating scientific ideas. The biggest evidence of this is Jancovici’s own writings. He published several traditional scientific books, but it was the comics that topped his book sales and book sales in France. Literature is characterized by imagination, visualization and creativity, and it helps science discover projects to achieve in the future.

* Wasn’t the book’s size an obstacle to translation?

The biggest challenge was finding a publisher in the Arab world who would accept the risk of buying the rights from the French publisher, and bear the cost of translation and illustration. Many of the drawings and figures in the book had been translated into Arabic. There were also problems with printing and distributing a 200-page book in large format and in color. For all these reasons, the adventure almost ended in frustration. Then a small miracle happened when I met Ms. Leila Chaouni, director of the Moroccan publishing house “Al-Fnak”, who is a human rights activist and advocate for women’s rights and freedom. She welcomed the idea, and saw that climate change is one of the issues that should be fought for, and that publishing the Arabic version is part of the commitment that a responsible publisher must have.

* Are you optimistic that this effort will reach a wide range of readers?

The book is intended for everyone. As the famous French phrase goes: “From seven to seventy-seven years old.” It is a family read and a reference in schools and universities, as well as in administrations and companies. The French version has made it easier to discuss energy resources and climate change, and has been a catalyst for discussion, exchange of opinions, and taking positions that would reduce the scourge of greenhouse gas emissions and global warming. The citizen is first and foremost a consumer, and in his hands is the solution to a global problem. This book shows how the individual contributes to finding a solution that helps humanity enjoy a better tomorrow.

COMMENTS