Since their existence on this earth, humans have never stopped fighting and slaughtering, and imposing control over each other, throu

Since their existence on this earth, humans have never stopped fighting and slaughtering, and imposing control over each other, through the bloodiest and most lethal means. Whether wars throughout history were waged as a result of ethnic, religious, and ideological conflicts and the desire for control and possession, or took the form of defending freedom and resistance against occupation, their disastrous results were not narrow to the destruction of homes, buildings, and material landmarks for living, but rather went beyond that to cause cracks in the human interior, and to cause a complete collapse in the human being. The system of values and rules of behavior, and to put a person’s relationship with himself and others open to doubts and questions.

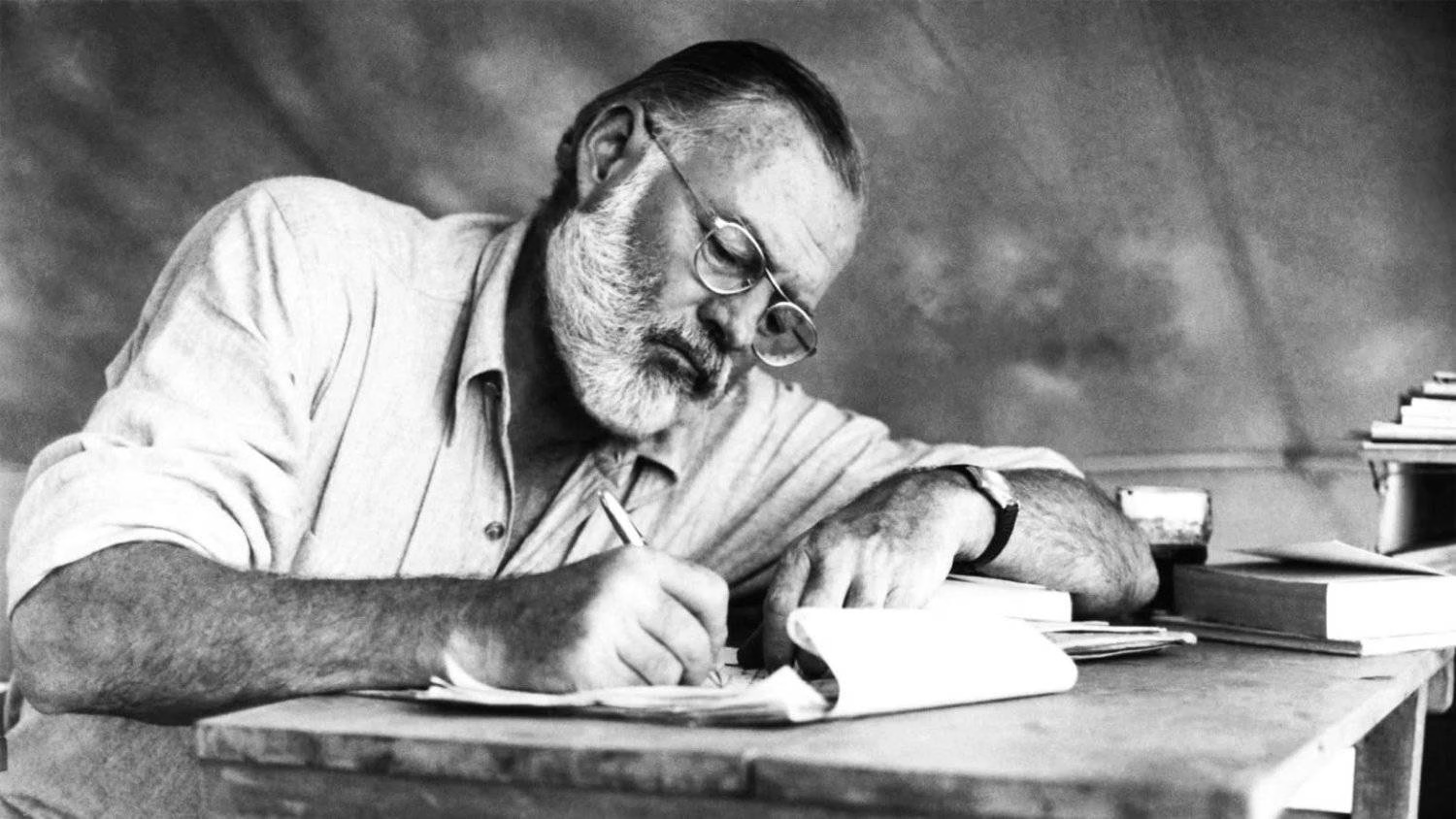

Hemingway

However, it is a remarkable paradox that the fierce wars that afflicted human society with the most horrific and horrific disasters are the same ones that provided philosophy, thought, and art with the most profound questions about the nature of the human soul, the motives of good and evil, and optimal social systems, in addition to their essential role in changing literary and artistic sensibilities. And push it towards modernity and renewal. If the question about the effects left by wars in the fields of literature and art is among the questions that critics and interested parties do not tire of asking with every novel war, then the problem that is constantly raised relates to the role of writers and intellectuals in times of war, and whether this role is narrow to producing… Texts and original works, or should writers and artists, by virtue of their national, national and humanitarian affiliation, defend the issues of their people in all possible ways and means?

If this type of question does not find definitive answers, because each person sees aspects of the truth that suit his positions and orientations, then returning to history may enable us to clarify some facts related to the positions of poets and creators regarding wars and civil conflicts, and what they did, outside of texts and works of art. Roles and contributions. Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind in this context is the pioneering experience of the pre-Islamic poet Zuhair bin Abi Salma, during the bloody war that broke out between the Abs and Dhubyan tribes, which was known throughout history as the war of Dahis and Al-Ghabra. Zuhair was keen to describe the war with appropriate epithets, warning of its disastrous consequences through his well-known verses:

War is nothing but what you have learned and tasted

What is it about in the translated hadith?

When you send her, you send her reprehensible

It will be harmed if you harm it and it will be ignited

The millstone’s lair will overwhelm you with its dregs

She fertilizes a scout, then she produces and is healed

However, Zuhair, who painted in his painting one of the most indicative paintings of the horror of wars and their catastrophic horror, saw that it was his duty, as a human being and as an individual in a group, to incite the rejection of violence and call for the liberation of souls from grudges and grudges. When he began to praise both of the advocates of peace, Al-Harith ibn Awf and Haram ibn Sinan, he did not do so out of flattery or seeking wealth and prestige, but rather he did so as a victory for their noble moral stances, and for the great sacrifices they made with the aim of extinguishing the flame of war and bringing peace between the disputing parties.

Although wars in their various forms have formed the most essential backbone for many epic and fictional works, the value of the work generated by them is not necessarily determined by the writer’s personal participation in battles and confrontations, but rather by his high talent and interaction with the event, and how to move it from the category of superficial and recorded descriptions to the category of deeper connotations. For justice, freedom, and the struggle between good and evil, all the way to human existence itself.

If the history of literature, both age-old and newfangled, is full of proofs and evidence that narrow the gap between the two disparate options, it is sufficient to return to Homer, whose blindness and inability to participate in wars did not prevent him from writing the epics “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” the two immortal masterpieces of literature. It is also possible to infer Tolstoy, whose novelistic masterpiece, “War and Peace,” was not the result of his direct participation in Napoleon’s war on Tsarist Russia, during which he was not yet born, but rather the result of his emotional interaction with the suffering of his people, and his insight into the cracks and disparities that govern human relations. . Although he had no choice but to join the army at a later time, he quickly turned into an advocate of love, rejecting violence, and achieving peace among people.

As for the other side of the options, it is represented by many different experiences, including the experience of the American writer Ernest Hemingway, who, throughout his busy life, provided the most shining example of the relationship between writing and life, and he was not satisfied with describing the war from a distance, as many writers did, but rather sought direct confrontation. With its risky fields, which was provided for him by his profession as a war correspondent for the newspapers in which he worked. In fact, Hemingway’s surplus muscle strength, and his national and humanitarian commitment, were not the only motivations for his participation in the wars he fought. Rather, his primary motivation was the search for a actual land to write his various novels and stories. If the writer’s vigorous involvement in World War I was what stood behind his early novelistic experience, “Farewell to Arms,” then his participation in the Spanish Civil War in defense of the Republicans, along with the great writers of the world, is what inspired him for his subsequent novelistic masterpiece, “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” ».

In the same context, we can put the experience of the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, whose great passion for flying prompted him to join his country’s air force, and the crash of his plane during one of the flights did not prevent him from continuing the adventure of flying until his tragic end in 1944. However, that flight In particular, he is the one who allowed Saint-Exupéry to paint, through “The Little Prince,” a picture of planet Earth, far from violence and full of childish purity.

The value of work generated by wars is not necessarily determined by the writer’s personal participation in them

There is, of course, much evidence, which this article cannot cover, of the different choices made by writers and artists in times of war, the debate over which is renewed with every war that takes place, or every confrontation that peoples engage in with their occupying invaders. If some original people see no reason for their existence other than creativity, and do not find anything to offer their countries in their moments of distress, except a poem, a piece, a painting, or other forms of expression, then others assign different roles for themselves, ranging from defending the land to those who are able to do so. In a way, between demonstrating and issuing statements denouncing the occupation’s crimes, massacres and atrocities, all the way to the writer’s personal contribution to alleviating the suffering of his people and providing them with reasons for resistance and steadfastness.

However, any talk about the role of writers and artists in times of war would be incomplete without referring to dozens of media professionals, photographers and correspondents in Palestine and Lebanon, whose bold field reports contributed to revealing the brutal nature of the occupation and exposing its false claims about adherence to the moral and humanitarian rules of war. . If it is completely impossible to recover the names of the many media professionals and correspondents who insisted on reconciling their professional and humanitarian duties, even if their lives themselves were the price, then it is sufficient in this context to remember the Lebanese writer and media personality Najla Abu Jahja, who took various pictures of the bodies of children thrown from the ground. The Al-Mansouri town ambulance, during the Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon in 1996, while at the same time keen to extend a helping hand to the wounded who remained alive. As Najla left this world, exhausted by a terminal illness, a few days ago, the extinguished eyes of children will not stop haunting her poignant images, renewing her contract with the featherlight, and distributing her enraged, accusing looks between the world’s lost justice and the faces of the executioners.

COMMENTS